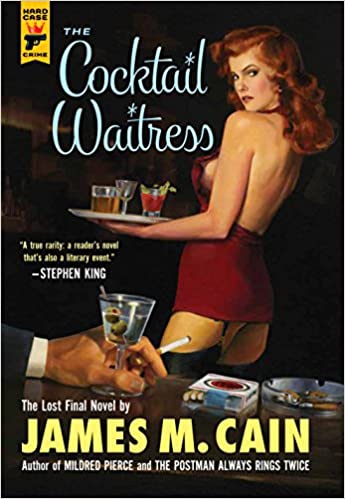

The Cocktail Waitress by James M. Cain

Tags: crime-fiction, noir,

The Cocktail Waitress was the last book James M. Cain wrote before he died in 1977. Hard Case Crime editor Charles Ardai pieced it together from a number of manuscripts and published it in 2002.

The book, as Ardai says, “is a classic Cain femme fatale story that’s told for once from the femme fatale’s point of view.” And what a point of view it is.

The book opens with twenty-one year old widow Joan Medford standing at her husband’s grave. She wears a heavy veil to hide the black eye her husband gave her before he drove drunk into a culvert wall at seventy miles an hour.

Joan’s life so far has been a disaster not entirely of her own making. Born to a wealthy family in Pittsburgh, her parents disowned her at seventeen when she refused to marry the boy they had chosen for her. Left to her own devices, she went to Washington, DC, in search of a job. This was the late 1950s, and there were few good prospects for an unmarried girl with no college education.

While living with a friend, waiting for a job to come through, she met the wrong guy, got pregnant, and got married. While she tried to make a go of it, with a child and a small house in Hyattsville, Maryland, her husband, Ron, expressed his frustration with the marriage through drunkenness and violence.

But he’s not the worst character we meet in the opening pages. Ron’s sister, Ethyl, unable to have children of her own, covets nothing more than Joan’s three-year-old boy, Tad. She takes the boy in, ostensibly as a favor to Joan, who needs time to find a job so she can support her child.

Ethyl, we soon learn, has no intention of giving the boy back. She begins an insidious, underhanded campaign to smear Joan’s reputation, to insinuate she killed her late husband, to make her appear to the world as an unfit mother. If you think men and women do bad things to each other in noir, they’re nothing compared to the things Ethyl does and says against her sister-in-law. The venomous, moralizing, self-righteous Ethyl, a paragon of middle-class convention with a seething snake pit for a heart, is one of the nastiest characters in all of noir.

In the first half of the book, we feel the constraints of mid-century sexism, rigid gender roles, and limited economic opportunity tighten like a noose around the soul of Joan Medford. To get her child back, she needs to earn a living, but the only job she can find with decent pay is serving drinks in a gin mill, where the waitresses wear short shorts and low-cut tops to encourage better tips from the male clientele.

While this provides a steady income, it plays into the hands of Joan’s sister-in-law, Ethyl, who smears her at every turn, painting her as immoral and unfit in an effort to keep custody of Joan’s son.

Joan soon finds herself faced with a choice, the kind of awful choice that too many women had to make in an economy that provided them little opportunity to make a decent living on their own. On one hand is a man she loves, young and impractical. On the other is a man with money, old and–though decent in nature–physically repugnant to her.

One can help her get her child back, at the cost of a lifetime of personal misery. They other is no sure ticket to anything except personal and perhaps fleeting joy.

Joan makes her choice near the midpoint of the book, and there things begin to twist. Cain is a master of both plot and character. The events of the story unfold so naturally and the scenes are so engrossing that you can’t see exactly what he’s setting up, though you feel the tension rising continually. Seemingly minor events come together in unexpected ways to bring poor Joan into the worst of circumstances.

And my belly began to tell me how deep my fear was. And then at last I began to realize how terrible a thing it was, the dream that you make come true.

Some people think of the femme fatale as an embodiment of feminine power, while others see her as a misogynist caricature. In The Cocktail Waitress, Cain lays out in painful detail how a combination of unfortunate personal experience, unyielding social strictures, and limited economic opportunity mold a reasonable, intelligent person into one of the dark archetypes of twentieth century fiction. By letting her narrate, he also shows she’s not at all what Ethyl and the gossip-mongers and the unsympathetic moralizers make her out to be.

If you’re coming from the lean prose of The Postman Always Rings Twice, it will take a while to adjust to Joan’s first-person narration. She’s not an inarticulate kid from the wrong side of the tracks. Her family was in the social register. She is articulate and self-aware, almost too articulate, too proper in her speech for the situation she finds herself in. And yet, here she is: a tough, smart woman making the best of a very bad hand and paying a heavy price for being tough and smart, for insisting on surviving and refusing to submit.