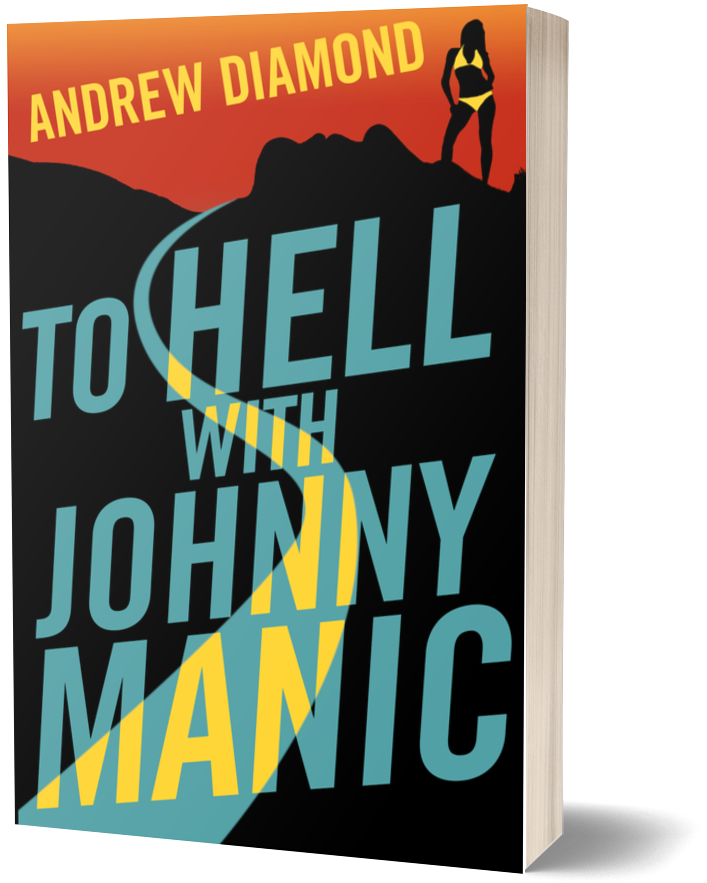

To Hell with Johnny Manic

Chapter 1

The merciless Vegas sun poured in past curtains I’d left open to spite myself, washing all the color from the room and poking its lurid fingers into the eyes of my champagne hangover.

This was the day everything was going to change. This was the day everything had to change.

Just like yesterday, and the day before, and the day before that…

I was down to the last two hundred and fifty thousand dollars of Manis’s money, and the way I was going, I could have lost it all in a single night. Maybe even in a couple hours. Or I might have hit a good streak and gone up half a million and stretched out my stay in that pampered hell for another month.

However it played out, I knew the end was near. I’d be broke, and I’d have to go out and earn a living again.

To be honest, the thought didn’t scare me. In fact, it was a relief.

I’d live in a modest apartment with an alarm clock that told me when to wake up. I’d go to work at the same hour as everyone else and go home when they went home. Pick up food at the grocery store, cook for myself, clean the kitchen, watch TV, go to bed. My life would go in circles, like the hands of the clock—constrained, predictable circles that kept trouble on the outside.

Another thing was bothering me. I mean, besides the money I’d wasted and the mess I’d made of the past few months. The legal guardian of John Manis’s father had been emailing me—emailing Manis—with dire reports about the state of the old man’s health. His cognition was shot. His moods were getting worse. “John, it’s sad. If you walked in, he wouldn’t recognize you. Some days, he doesn’t even know he has a son.”

The facility he was in couldn’t handle a case like his. The nurses and orderlies snapped at him and that made him even more agitated.

Lord, I understood that feeling. Every place I’d been in since I returned to the States felt like the wrong place, and I was always agitated. But unlike old Mr. Manis, I had some distraction. I could gamble it off. I could drink it off. I had a new group of best friends every night. I’d treat them to a fifteen-hundred-dollar dinner and make sure they were all charmed by the smooth, attentive, flattering, and charismatic John Manis.

Everybody loved John Manis, and no one gave a damn about Tom Gantry. That bugged me too. Tom Gantry was lonely as hell, the invisible heart of a seemingly charmed life, all by himself in a world no one could see or understand. Just like Manis’s old man.

I called the legal guardian right there from the bed, before I got dressed, before I could get distracted or lose my resolve.

“John? Wow! We finally get to talk.”

That was a relief. He didn’t know Manis’s voice.

He told me the old man’s body was still strong. “That’s the saddest part. Usually when the mind is this far gone, they only have a few months to live. He could have another year or two.”

He repeated the info he’d sent in the emails. The memory care facility that specialized in cases like his cost ten thousand a month on top of what Medicare paid.

“I’ll wire you the money. Two hundred and forty thousand,” I said, trying to blink away the sting of the insolent sun. Why hadn’t Manis done this himself a year ago? Why hadn’t he visited the old man, for Christ’s sake? If I had a father, I sure as hell wouldn’t let him languish like that.

“You don’t have to wire it,” the guardian said. “You can set up a monthly draft.”

“No. I’ll send it today.”

I had to, or else I’d blow it all that night. Two hundred forty thousand would carry old man Manis for a full two years, if he lasted that long.

That left me with ten thousand. I wouldn’t have to pay for the room because the casino would comp it after all I’d lost. Their way of saying thank you, come again.

The only problem with leaving was I had nowhere to go. I could be on the road in thirty minutes, but which road? Going where? The old panic was starting to rise, and it came up slowly this time, from the depths, like a freight train gathering steam.

That meant it was going to be a bad one.

Do something, Tom!

Do what?

Something. Anything. Get out!

This was the urgency, the compulsion that had earned me my nickname at the gambling tables. The calm, well-dressed guy who arrived with a smile was John Manis. Everybody’s friend. The frantic one throwing the dice and dramatically promising the crowd he’d win this time was Johnny Manic.

The real John Manis, who by now was long gone, was the guy who’d written all those addictive games that kept people glued to their phones, stacking colored jewels, running through mazes, and abusing barnyard animals. He’d sold out at age twenty-seven to a big gaming company and then posted an online manifesto denouncing the evils of the technology that had made him rich. In his dramatic middle-finger farewell to the twenty-first century, he deleted his social media accounts and told the world he was going off the grid forever.

That last part wasn’t true. When I met him, he owned a cell phone and a laptop for trading stocks on E*TRADE.

But his story struck a chord among the tech workers who slaved endless hours in hopes of striking it rich. For two days, his manifesto sat on the front pages of Reddit and Hacker News while code jockeys in cubicles across the country gossiped about the lucky genius who had struck gold and then walked out on his own life.

That was two and a half years ago, and I still occasionally ran into computer programmers who said, “Wait, you’re John Manis? The John Manis who wrote Emerald Crunch and Birdapult and Frog Slap? I thought you were, like, just a legend.”

Manis would have liked hearing that. His myth was more important to him than his money. He used to say he was the greatest programmer nobody ever met.

And he would have liked to see the panic that was rising in me as I tore through the pile of clothes on the floor.

“It’s not easy being me, is it, Tom?”

“Shut up, John.”

It wasn’t just the smugness of his tone that bothered me. It was the clarity of his voice, like he was right there in the room.

“You can’t just put on my clothes and my mannerisms and expect to pull it off. This isn’t a game of dress-up.”

“Shut up!”

What irked me most about him, and what I admired most, was his impossible self-assurance, his unshakable confidence. The man was always at ease.

I dressed without showering, without shaving, without even brushing my teeth.

Pick the grey suit, I told myself. You’ll look more composed.

I checked the mirror to see how composed I looked. The strain and excess of the past few months had puffed out in great dark circles beneath my frantic, flashing eyes. But the suit looked great.

Now get out of here, I told myself. Before you lose your nerve.

I don’t remember being in the elevator, but I do remember the bustling lobby. I do remember singling out the blond-haired kid with the jeans and the black skateboard t-shirt. Jason. It was like he had a spotlight on him, like the universe was pointing him out to me, saying, That’s the one you need to talk to.

I had had dinner with him two nights before, and what was it he said? His girlfriend got into grad school in Boston. He was moving east. He had a one-man business back in California, driving up and down Napa Valley helping old folks set up computers and Wi-Fi networks, cleaning viruses off their hard drives, making sure their printers could spit out photos of the grandkids. He had hoped to sell the business before he moved, but the deal fell through.

Why not sell it to me, I thought. I understood the basic tech stuff well enough. And it would give me a destination. At least I’d know which way to point the car when I drove out of town.

“Hey!” I was right in front of him now. His eyes lit up when he saw me. “You still looking to sell that computer business?”

He put on a mock frown and shook his head. “It’s not happening,” he said.

“No, I mean, will you sell it right now? To me?”

He looked confused, and I understood why. John Manis was a high roller, winning and losing more on one throw of the dice than his business earned in a month.

“Dude. You don’t have to pity me. We have enough to make it to Boston.”

“No, I’m serious.” I tried to look earnest, but his expression told me I might have looked a little crazy.

“Yeah, well, it’s not, like, an investment.” He put on a sheepish smile. “It’s just a getting-by kind of business. You wouldn’t want it.”

“I want it,” I said, trying not to look as desperate as I felt.

“Look,” I added in a quieter voice. “I know what you think of me, but I have to get out of here. I need a job. Something stable to bring me back down to earth.”

He hesitated for a moment, like he thought I might be putting him on. When it dawned on him that I was serious, he looked concerned, almost disappointed.

“But,” he faltered. “You’re John Manis. You wrote those games. You have money.”

“Had,” I said. “I blew it.” And I couldn’t help adding under my breath, “Just like I blow everything.”

He heard that, and his look of disillusionment threatened to melt into pity. Hadn’t I spent a whole evening filling his head with stories of my travels? Wasn’t I the one who treated him and his girlfriend and whoever those other two people were to their first four bottles of Dom Perignon?

“I’ll give you five thousand for it,” I blurted. That was half of what I had left. “That’ll help you and your girlfriend get set up in Boston.”

The way he smiled, I knew I could have had the business for a thousand.

I was going to pay him right then and there, but he said, “I don’t want to take your money. You don’t even know if you’ll like that part of California—”

“I’ll like it,” I said.

“—or if you’ll like the work. It might bore you.”

He gave me his card—The Computer Kid—and told me to check out the town in Napa. He’d meet me there in three days to give me a tour and introduce me to some of his regulars.

“But call me before then if you want to back out,” he said.

“Yeah, sure.”

We shook on it, and the kid floated off in search of his girlfriend.

I went back upstairs and packed. The laptop, six suits, a few extra pairs of slacks and shirts. All top-of-the-line designer labels that reeked of John Manis and his ingratiating charm, his infinite self-assurance and colossal arrogance. I told myself when I got to California, I’d sell the suits on consignment, buy a few pairs of jeans and some t-shirts, and ease back into Tom Gantry.

But I’d still have to be Manis in name. I had his license, his passport, and his spotless record with the law. Manis was employable. Tom Gantry, the fugitive embezzler who’d violated parole in Illinois, was not.

After wiring two hundred forty thousand dollars back to Maryland, I drove the north road out of Vegas in an aqua-green 1963 Corvette convertible, through the sun-bleached desert that skirts the eastern edge of Death Valley. I crossed into California near Lake Tahoe just after sunset, winding through corridors of dark Sierra pine in the crystalline twilight of a cool mountain evening.

The scent of tree sap and pine needles swelled my heart with hope. The arid wasteland was behind me. Before me was a new country, lush and green.

I’d push through to Napa in one straight shot, and in the morning I’d awake far from the empty desert and the garish oasis of excess that brought out the worst in Johnny Manic