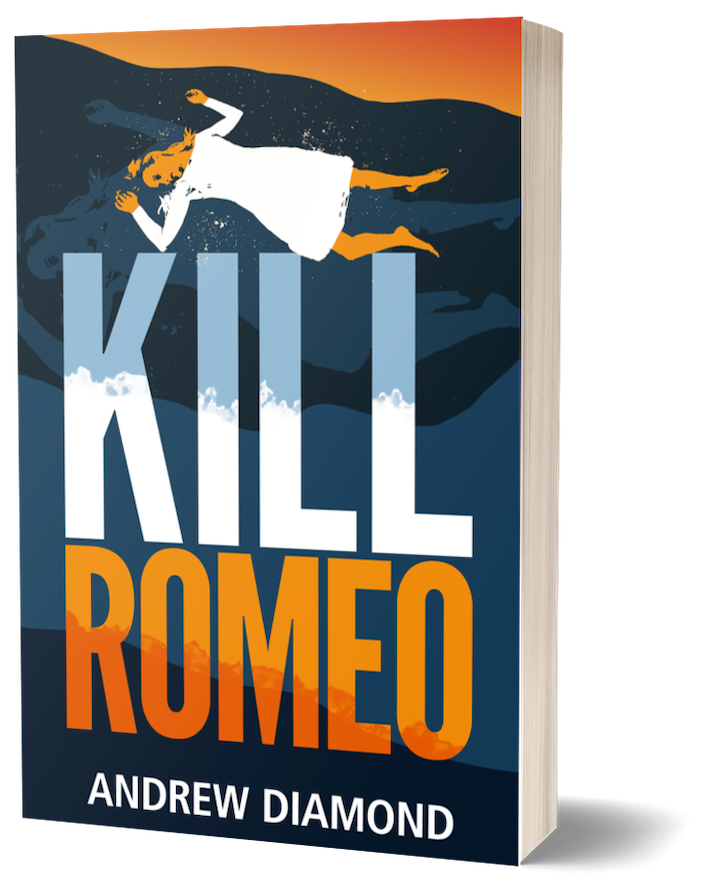

Kill Romeo

Chapter 1

August 19

Nelson County, VA

If I had known how fast the storm was coming, or how strong it would be, I would have turned around sooner. The dog would have to find his own way home. His owner, Mrs. Jackson, told me he always did.

We were on the east side of the mountain, the storms were on the west. The peaks of the Blue Ridge muffled the rolling thunder.

The trail was muddy and the bark of the trees was still wet from yesterday’s rain. Sweat plastered my jeans to my legs. The dog, an overly excitable yellow lab, had been running circles around me, snuffling through the leaves on the trail of a fox or raccoon before he disappeared.

I heard something coming fast up the trail behind me. I knew there were bears in these mountains, but I didn’t think they could move that fast.

I turned, ready to fight—my instinct is never to flee—only to see the dog galloping toward me with a bright white animal clenched in his teeth.

He reached me, breathless, dropped it at my feet, and barked four times, eyes lit with excitement.

At first, I couldn’t make sense of it. An animal that small, that white, dropped from the jaws of a dog, with no blood on it. You know when you stare at something you’ve seen a thousand times but your mind can’t place it? A familiar thing in the wrong context, in a place where it doesn’t belong…

I knelt and picked it up, felt the contours in my hand. It took a second to click. A woman’s shoe. A white satin shoe, flat-soled and clean, except for the dog slobber. How could it be up here in these woods and not be muddy?

The dog barked loud and hard, his front legs wide and low, tail straight up. They can tell you things in their crude and primitive way. The fundamental, important things that matter to all living creatures, they can tell you.

That shoe belonged to someone.

He turned, ran down the path, stopped to see if I was following.

A violent wind raked the forest as we descended. The storm that seemed miles off five minutes ago was suddenly on top of us. The tops of giant, thick-trunked trees swayed like willows. Stray leaves blew down the mountain, flipping green over silver. I followed the dog straight down the fall line, cutting across the snaking trail. The dog veered right as the first, fat drops began to fall, and the muddy trail disappeared behind us.

We followed a narrow stream to a pond in a clearing, stopped up at the far end by a pile of branches and trees. This was the beaver dam that Mrs. Jackson had told me to avoid. It had too much water behind it and was in danger of breaking. The forest service had already removed the beaver and was going to dismantle the dam. Until they did, the trail below it was closed.

The skies opened up as the dog rounded the pond. Rain poured down in thick, deafening sheets. I slipped in the muddy leaves trying to keep up with him, went down twice and came back up just as quickly, the rain bleeding the mud out of my jeans as fast as I could dirty them.

The dog circled back, collected me, and as he led me toward the dam, the air flashed purple. The crack of lightning shook my sternum like a drum, and in the flash, I saw the dog’s tail tuck between his legs as he tore off in terror.

I stood beside the dam, scanning for him. Little streams began to appear everywhere, washing leaves from the forest behind me into the clearing. The narrow creek that fed the pond began to swell and turn white.

Where was the dog? I looked toward where I’d last seen him, but my eyes couldn’t pierce the grey-white curtain of rain.

There! Bolting back from the woods he’d fled to in terror, back into a grassy clearing below me, his tail still tucked, still terrified. He stopped at a figure in white by the edge of the stream forty yards below the dam and hung his head, as if he’d given up.

I slipped and slid though weeds beaten down to mud by the relentless rain. The dog, panting and somber, ears and tail down, gave me a woeful look. The woman, dressed in white, lay on her side, left arm outstretched beneath her head, like she had fallen asleep. The rain had matted her hair, exposing dark roots beneath the blond dye. I guessed she was in her late twenties.

She wore a lightweight white cardigan, white blouse, knee-length white skirt, and one white satin shoe. Her eyes were half open, light brown with a dark ring around the iris.

Her face was blue. She had no pulse. I checked her hands and forearms for defensive injuries. Not a bruise or a scratch. No wounds on her legs, face, or neck.

She wore a silver necklace with a turquoise stone. No rings. No earrings. Around her right wrist was a thin black leather strap.

The stream that had been ten feet away half a minute ago was now five feet closer and continuing to swell as water spilled over the dam above.

I circled to the woman’s back side—her back was to the water—crouched, pulled at the fabric of her sweater and skirt, looking for blood. Nothing.

The dog was whining now. He pawed my knee as I stood. I think he was scared and wanted to leave.

Who dresses like this in summer? Not someone who’s going into the woods. Not someone who’s planning on being outside in the muggy August heat. With that thin white sweater, she was going to lunch or a movie, to some place with air conditioning. And she couldn’t have walked up here in those flat treadless shoes. The muddy paths were too slippery. And this path, leading up to the beaver dam, was closed, blocked off at the bottom by the Park Service.

Her bare left foot was blue. I took the shoe off the other foot. Also blue.

I went back to her front side, knelt and rechecked her hands. Blue, like her face and feet. Like she’d been carried up here, a fireman’s carry, the cyanosis setting into her extremities as she was folded over someone’s shoulder.

She began to move.

The dog swatted my shoulder with his muddy paw as if to say, Come on, let’s go.

How could she be moving? She was blue as death.

I reached for her wrist, checked again for a pulse before I realized it wasn’t she that was moving. It was her skirt. The stream had widened five more feet in less than a minute and was pushing against her skirt.

Water poured over the top of the dam upstream, carrying branches with it. The dam was going to burst.

The dog swatted me again, hit me in the face this time as he barked his urgent warning. Get out!

And then the sound of wood cracking, like a building collapse. It unleashed a thunderous torrent of water.

I tried to pull her up to higher ground. I had her by the wrist, and I could have done it if we had had more time. I’m a strong man. A very strong man who used to make his living in the ring, beating up guys no one in their right mind would ever want to fight. I could have pulled her like a child pulls an empty wagon.

But the water got her before I could take a step. Pulled her down the hill and took me with her.

The first two branches from the dam hit me. One in the head, one on the right shoulder. But I didn’t let go. I still had her wrist.

The next branch was a big one. Maybe a small tree. It hit the crown of her head so hard it must have broken her skull and neck. Knocked her right out of my grasp. The last I saw of her, she was tumbling head over hips through white water and black branches, her head wrenched sideways on a badly broken neck.

The rush of water slammed me into the trunk of a thick tree. I bounced off toward the outside of the stream, away from the raging center.

A branch hit me in the head and knocked me under, but I came right back up. The dog followed me down, running along the stream’s edge, his frantic barks loud and sharp in my ear.

The water pushed me down another two hundred yards or so and pinned me against a couple of saplings that bent heavily under my weight and the force of the stream. I was stuck there for a few seconds before a clump of branches from the dam snagged on a rock just upstream.

The dog barked furiously at the water’s edge. Get out! Get out!

The snag of wood diverted the flow away from me and took enough pressure off for me to move. I planted my feet, grabbed a sapling with my left hand, and pulled myself up. I didn’t want to use my right. There was something in it I didn’t want to let go of.

I made it to the water’s edge and up a steep embankment before the catch of wood broke free, releasing a torrent that flattened the saplings I’d been pinned against.

I sat there breathing heavily, watching the world wash away as the dog licked my face. He was so happy, you’d think I’d just saved his life, not my own.

My body ached like it used to after fights, only now, parts of me were hurting that boxers aren’t allowed to hit. The back of my head, my kidneys, my legs, the soles of my feet. Something had hit me hard under the right armpit. I didn’t remember it happening, but I felt it now, the swelling and raw skin. A huge bruise was beginning to form.

I sat exhausted, breathing heavily, waiting for the adrenaline to wear off, waiting to regain my strength. The dog kept licking my face like he was trying to remind me I was okay. After twenty minutes, the clouds thinned and the winds calmed. The rain seemed to stop, though drops still fell from the leaves above.

The dog nudged his nose against my ear, as if to say, Come on, let’s get out of here.

These woods were his stomping grounds. He knew the way back to Mrs. Jackson’s. And he knew to leave me alone for a minute when I opened my right hand to look at the last piece of that poor woman I still held on to. The thin leather strap around her right wrist had come off when the stream pulled her out of my grasp.

It was the kind of strap kids use to make bracelets and necklaces at summer camp. It looked like she had tied the knot herself, and it had held, even through the flood, until it finally slipped off over her hand and into mine.

The most interesting part had been hidden from me when I found her lying in the grass. It must have been beneath her then, pressed between her skin and the wet grass. A little brass key just big enough to open a padlock or a gym locker. A key imprinted with a black seahorse and the number 212.