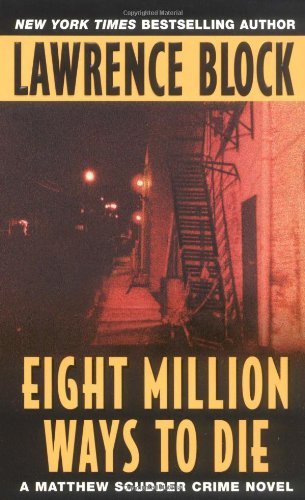

Eight Million Ways to Die

Tags: detective-fiction,

Eight Million Ways to Die is the fifth in Lawrence Block’s Matthew Scudder detective series. You don’t need to have read any others in the series to follow this one.

Scudder is a former New York City cop who quit the force after accidentally killing a child while pursuing two thieves. By the time the book begins, he has long since left his family, and has been living for years in a mid-town Manhattan hotel. He makes his living under the table, as a cash-only unlicensed detective. His training helps him out, as do his connections on the force and on the street. His chronic drinking hinders him.

The story begins with Scudder in his favorite bar, talking to a prostitute who wants to get out of “the life.” She’s afraid to talk to her pimp, Chance, about leaving, and wants Scudder to feel him out first.

The pimp is not an easy man to find. While trying to track him down, Scudder has the following exchange with his informer, Danny Boy. The informer asks, “What can I do for you?”

“I’m looking for a pimp.”

“Diogenes was looking for an honest man. You have more of a field to choose from.”

“I’m looking for a particular pimp.”

“They’re all particular. Some of them are downright finicky. Has he got a name?”

When Scudder manages to track him down, he finds Chance is no ordinary pimp. He’s reserved, thoughtful, well-spoken, and introspective.

After Scudder finds the pimp has no objection to his client’s leaving, the prostitute is brutally murdered in a Manhattan hotel room. The pimp, obviously, is the prime suspect. The only problem, though, is that he has an airtight alibi.

With no other suspects to pursue, NYPD lets the case languish, but Scudder isn’t willing to let it go. The pimp returns and hires Scudder himself to find the killer.

That’s the setup. Most of the action involves Scudder doing old-fashioned detective work, what Scudder calls “goyakod”: Get off your ass and knock on doors. We then follow the detective through a number of encounters with cops, pimps, prostitutes, artists, witnesses, and drinking buddies in three of New York’s five boroughs.

The book is heavy on dialog, which is one of Block’s strong points as a writer. He doesn’t need to spend much time on backstory to develop rich characters. He reveals a person’s perspectives, attitudes, and temperament through their speech.

Eight Million Ways to Die was published in 1982 and takes place around that time. Much of the book is a meditation on the state of New York City, and if you spent much time in the city in the late ’70s and early ’80s, you’ll find that Scudder’s narrative brings the old city vividly to life.

New York in the late ’70s, with its filthy streets, its grafitti and general slovenliness was the urban incarnation of a hangover. By the early ’80s, crime was rampant and seemed to be getting worse every day.

Scudder begins most of his days reading the news, which seems to be a catalog of human depravity. The title of the book comes from his reflection, after reading about a number of murders, that in a city of eight million people, there are eight million ways to die.

He spends much of the book working with an NYPD homicide detective named Durkin, a cop who has seen too many of the things cops see, and who bitterly laments the decline of the city. Many of Durkin’s complaints echo those of today’s political right: the influx of poor and struggling immigrants from all corners of the world has transformed the city into one he hardly recognizes. Many of the city’s new arrivals, it seems, have brought with them the troubles they were hoping to flee.

Durkin complains that when he goes on the subway he feels like he’s in a foreign country. He is overwhelmed by a world he can no longer comprehend, and he confides to Scudder that he can’t wait to retire. Trying to keep order in such a vast, unruly city has sapped his energy to the point where he just wants to withdraw.

As he tracks down the clues to the prostitute’s murder, Scudder spends an enormous amount of time and emotional energy contemplating his alcoholism and trying to resist the temptation of drinking. He admits that part of the reason he wants to keep working the murder case is to keep his mind off booze.

I won’t say how the investigation pans out, since that’s the mystery the reader signs up for when he or she picks up the book. I will say that like most good mysteries, the story isn’t about the crime or even the solving of it. It’s about a time and a place, the psyche of the main character, the world he inhabits and the lens through which he sees it. It’s about a violent, paranoid city in decline after Son of Sam, and the struggles of one of that city’s eight million souls as he tries to come to terms with his personal demons. Its final scene, one of the most famous in all of detective fiction, tells you it’s a book about character. And it’s well worth the read.