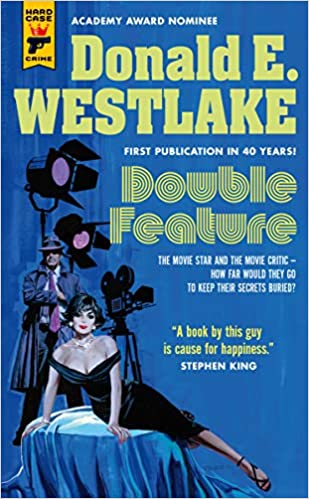

A Travesty, by Donald Westlake

Tags: crime-fiction, detective-fiction,

A Travesty is the first of two short novels in Donald Westlake’s Double Feature. The story opens with New York film critic Carey Thorpe looking down at the body of the girlfriend he’s just accidentally killed in her own apartment. A series of thoughts run through his mind, most of them converging on self-preservation: how can he get out of this mess without being fingered as the killer?

Well, no one saw him walk in. And no one knows he and the deceased, Laura Penny, have been dating. Thorpe has kept their relationship secret to avoid upsetting his other girlfriend, Kit Markowitz. He decides to gather his belongings and leave. Someone will find the body someday, but no one will ever know he was there, and no one will be able to tie him to the crime.

The next day, however, Thorpe gets an unexpected visitor. As it turns out, Laura Penny was married. Her husband had hired a private investigator to follow her, and the investigator, a tough, burly man named Edgarton, snapped a photo of Thorpe leaving the building with all his belongings after the murder.

Edgarton tells Thorpe that for ten thousand dollars, he’ll hand over the incriminating photo and edit Thorpe’s visit out of his official investigator’s report. Thorpe agrees, reluctantly, and then, in a surprising and devious twist, turns the tables on his blackmailer.

Westlake wastes no time getting his story rolling, as all of this happens in the first chapter.

Carey Thorpe is a deeply self-centered character. He’s not particularly likable, but when his dark, twisted humor begins to emerge in the second half of the book, he’s profoundly entertaining.

When the cops question Thorpe about the victim, they let him know he’s the only suspect they’ve crossed off their list. He’s definitively in the clear, thanks to Edgarton’s falsified report.

Thorpe’s guilty conscience, however, keeps him on edge. Every time he needs to calm his nerves, he washes down a Valium with a shot of bourbon. This is 1973, after all, when Valium was prescribed liberally and eaten like aspirin.

The problem, however, is that the Valium soothes his nerves a little too much. He should be taking his situation a lot more seriously. He should not be getting too chummy with the lead investigator on the case, Detective Sargent Fred Staples. But he Staples take a liking to each other, and Staples invites him to help out on a number of Manhattan homicide cases.

Thorpe tags along on some of the crime scene investigations and shows an expert detective’s eye, picking up on subtle clues Staples misses, and helping to solve some tough cases.

Staples keeps circling back to the Laura Penny murder. As the list of possible suspects dwindles, Thorpe gets increasingly uncomfortable. He worries that at some point, all of the other suspects will be exonerated, and Staples may turn his attention back to Thorpe.

Then that little twist from the first chapter comes back to haunt him. The private investigator, Edgarton, is a nasty character who resents the way Thorpe played him. On top of all this, Thorpe’s other girlfriend, Kit, is begins to investigate, and she’s a sharp one. Sharp enough to make Thorpe worry.

So what’s a guy to do in this situation? The deeply self-centered, Valium-addled Thorpe decides to blow off some steam by having sex with Patricia Staples, the equally self-centered wife of the lead detective, a woman “as beautiful and as intelligent as a sunset.”

The affair begins on an inauspicious note. Thorpe has just murdered an unexpected visitor and is stuffing his body into the bedroom closet as Patricia knocks at the front door. It doesn’t take long for the two to get together. Thorpe shows a rare note of self-awareness as he describes their tryst:

It was the first time I’d ever made love to a woman in a bedroom with a murder victim hanging in the closet, particularly a victim of my own, and I must say it made absolutely no difference at all. I was neither turned off nor were my responses heightened. Possibly I’m abnormal.

When Patricia’s husband, Sargent Detective Staples, happens by a few minutes after she leaves, Thorpe reflects:

If you’re going to commit a murder–and in the first place, I don’t recommend it–one thing you should definitely not do afterward is have sex with the investigating officer’s wife. It merely makes for a lot of extraneous complication.

The funniest parts of this book are Thorpe’s descriptions of Manhattan and its inhabitants in 1973. After he and Kit grab coffee at “a health food restaurant on First Avenue frequented by heroin addicts,” they invite all the suspects in the Laura Penny murder to a cocktail party, where Kit plans to interview them and suss out the killer.

Even Thorpe’s throwaway descriptions are funny. To their party of fashionably dressed Upper East Side elites, one woman brings a date who doesn’t fit in:

…a lurking shifty-eyed fellow introduced as Lou, who had long graying hair and heavy bags under his eyes, who wore dungarees and a flannel shirt and a leather vest, and who looked generally like an unsuccessful train robber.

Eventually, the walls close in on Thorpe. He doesn’t truly realize what a mess he’s in until the Valium runs out.

I had by now been living a Valium-free existence for nearly a week, and it was astonishing what a difference it made in moments of stress. What did Mankind do before these wonderful pills? Reality is drabber and slower and grayer without them, but the scary moments are suddenly faster and far more terrifying… Consequences seemed more real, dangers more possible. Valium had made it possible for me to walk my tightrope as though there were a net. Now, the chasm yawned plainly beneath me.

A Travesty ends with one final twist, which is both satisfying and a travesty in itself. If you like the dark, psychopathic humor of Jim Thompson, minus the disturbing violence and gore, you’ll enjoy this one. Kudos to Hard Case Crime for bringing this back into print.

For a review of the second half of this book, see my review of Ordo.