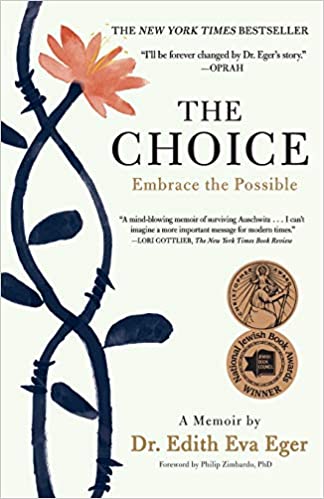

The Choice by Edith Eger

Tags: non-fiction, psychology,

Dr. Eger gives a powerful and harrowing account of her youth, of being taken from her home in Hungary, herded into the cattle cars, separated from her parents at Auschwitz. She and her sister survived more than a year in the death camp, and for months more on the death marches that followed before an American GI lifted her from a pile of corpses. Hope and remembrance of the good in life sustained her through unspeakable horrors.

After the war, she came to the US and eventually became a psychologist, helping others through hardship and trauma. Her message is simple, though it’s a hard one for many people to realize, and requires vigilance and effort in practice. We don’t always have a choice about what happens to us, but we do always have a choice about how we respond.

Bad things happen to everyone, and horrible things happen to many people. How well we recover after the fact depends in large part on how we choose to respond, how we choose to see ourselves and the world. She gives a number of examples from her own life, and from patients she has treated.

The first half of the book covers Eger’s early life in Europe, and it’s one of the most powerful stories I’ve ever read. It’s also unusually well written, with clear, precise prose that deepens the impact.

In the second half, she describes her new life in the US and having to go through the ordinary struggles that we all go through: finding work, getting along with her husband, worrying about an uncertain future. Even after surviving Auschwitz, these seemingly mundane things are still hard.

She begins her calling in life, clinical psychology, around age fifty, and by then she’s well equipped to help even the most troubled people. There’s nothing she hasn’t seen or been through. She doesn’t just see her patients' problems from the outside, she’s walked through the hell they’re in and has come out the other side. Now, she’s become a guide, and she knows from decades of hard personal experience that mental health isn’t about answers, it’s about practice and unceasing work.

The first part of that work, the breakthrough to which she must lead all her patients, is realizing that they do have a choice. This can’t be taught like the math or physics. Everyone must discover it individually. The hard work follows from there, and it’s mostly up to the patient to practice it, but once the realization sets in–the realization that they do have choices–the will to change comes with it.

This is a deeply engaging, moving, and meaningful book. Read it.