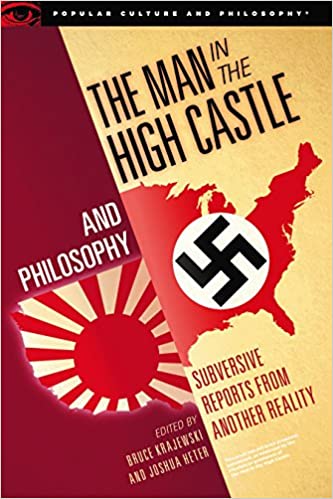

The Man in the High Castle

Tags: sci-fi,

Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle presents an alternate reality in which the Allies lost World War II and the Axis won. The book was written in, and takes place in, the early 1960’s. Unlike many of today’s dystopian alternate-history novels, which tend to be dark and somber, Dick’s story is darkly humorous.

Instead of focusing merely on how the victors oppress the vanquished, Dick transposes the absurdities and petty quarrels of twentieth century life onto an America colonized by Japan, a world in which two cultures, fundamentally at odds, must coexist without being able to fully understand each other.

Most of the story takes place in San Francisco, PSA (Pacific States of America). The Pacific States are under Japanese control, while the East Coast belongs to Nazi Germany. The Midwest and the Rocky Mountain states are still free.

Unlike the Nazis in the eastern US, the Japanese rule the PSA with a relatively lenient hand. They’ve taken the good jobs and the good neighborhoods from the whites, whose relation to their new overlords is similar to that of any colonized people to an imperial occupier.

The white characters, like the antique store owner, Mr. Childan, try to assimilate to Japanese cultural norms–bowing in greeting, speaking respectfully with carefully considered words, saving face in awkward social situations, gift-giving. Most of the time, they don’t get it right.

The sometimes frustrating and often funny daily struggles of Mr. Childan, the artisan Frank Frink, and his estranged wife Juliana are easy enough to identify with. The world they live in isn’t all that different from our own. When the larger historical forces begin to impinge on their lives, the book gets interesting.

Japan and Germany are engaged in a cold war. Relations are cordial but tense, and everyone–from those at the very top of society to those at the bottom–is impacted by the political machinations of the two regimes.

At the center of this book are two other books: The I Ching, which both the Japanese and the newly vanquished Americans consult as an oracle, and The Grasshopper Lies Heavy. The latter is an alternate reality novel depicting a world in which the Allies won the Second World War. It’s a bestseller in the free Midwestern and mountain states. The forbearing Japanese, yin to Nazi Germany’s yang, tolerate the novel in the Pacific states, while the rabid totalitarian Nazis have banned the book in the east.

The Man in the High Castle refers to Hawthorne Abendsen, the prescient author of The Grasshopper Lies Heavy. The alternate reality portrayed in his book pretty closely describes the actual post-war reality that readers of the outer book inhabit. (Dick’s readers, that is. You and I.) The world it portrays is fascinating to the characters of the inner book, who can’t imagine history turning out so differently. The course of history has cut off their imaginations. The fact that the inner book, Grasshopper, can restore that lost vision is deeply threatening to the Germans.

[Spoiler alert.] When Juliana Frink makes a pilgrimage to visit the man in the high castle, she asks him how his novel could create such an accurate alternative world. He tells her he consulted The Oracle, the I Ching, on every plot point, every character, every event. The five-thousand-year-old oracle embodies a complete understanding of human life, valid across all cultures and time periods.

This is Dick’s world of fun house mirrors: The reader reads a book about an alternate reality in which the characters are fascinated by a book about the reader’s reality, and that book was written by an older book about a timeless reality. [End of spoiler.]

The deepest, most interesting, and funniest character in the book is the Japanese bureaucrat, Mr. Nobusuke Tagomi. In his inner monologues–spoken in a pidgen Japanese-English that omits most pronouns and articles–we hear a sensible Eastern mind trying desperately to make sense of the out-of-control West. The Nazis represent the most assertive, hyper-masculine, controlling aspects of western society, an uber-yang totally at odds with Tagomi’s yin sensibilities.

When the Nazis send a gang of thugs into Tagomi’s building to assassinate a wayward German emissary, Tagomi calls the local German police headquarters to complain. As he picks up the phone, the generally soft-spoken Tagomi reminds himself that there’s only one way to be heard by the Germans: “Vituperate in high-pitched hysteria.”

His countryman smiles and urges him to “Put on good performance.”

When a Nazi flunky answers the call, Tagomi shouts, “I am ordering the arrest and trial of your band of cutthroats and degenerates who run amok like blond berserk beasts, unfit even to describe! Do you know me, Kerl? This is Tagomi, Imperial Government Consultant. Five seconds or waive legality and have Marines’ shock troop unit begin massacre with flame-throwing phosphorous bombs. Disgrace to civilization.”

Tagomi later reflects on the violent assassination attempt:

Whole situation confusing and anomalous, he decided. No human intelligence could decipher it; only five-thousand-year-old joint mind applicable. German totalitarian society resembles some faulty form of life, worse than natural thing. Worse in all its admixtures, its potpourri of pointlessness.

Where in this composite being is its sense? Who really is Germany? Who ever was? Almost like decomposing nightmare parody of problems customarily faced in course of existence.

The “five-thousand-year-old joint mind” refers to the I Ching, which can explain the human world because it brings a perspective broader than any one individual’s, broader than any particular time or place or culture.

Tagomi is as funny as he is insightful. Like many of us, he’s always trying to make sense of a world that doesn’t quite make sense. At one point, unable to understand why a silver earring is beautiful, he loses patience, shakes it violently and commands, “Yield, silver triangle! Cough up arcane secret!”

Like many others in the book, he comes to realize “One cannot compel understanding to come.”

Even the German emissary, Wegener, the target of the assassination attempt, has his moments of doubt in a world gone mad:

The terrible dilemma of our lives. Whatever happens, it is evil beyond compare. Why struggle then? Why choose? If all alternatives are the same…

Evidently we go on, as we always have. From day to day. At this moment, we work against Operation Dandelion. Later on, at another moment, we work to defeat the police. But we cannot do it all at once; it is a sequence. An unfolding process. We can only control the end by making a choice at each step.

We can only hope. And try.

On some other world, possibly it is different. Better. There are clear good and evil alternatives. Not these obscure admixtures, these blends, with no proper tool by which to untangle the components.

We do not have the ideal world, such as we would like, where morality is easy because cognition is easy. Where one can do right with no effort because he can detect the obvious.

In a number of interviews, Dick said that much of his early writing was fueled by heavy amphetamine use. It shows in this book, not in breathless or hurried prose, but in the rate at which he presents profound ideas, philosophical observations, and deep insights. His mind operates on a deeper level, across more dimensions than most popular authors. Maybe he needed the speed just to get it all out.

Though it takes a while to get into, this is an unusually entertaining and thought-provoking book. I’ll probably come back for a second reading.