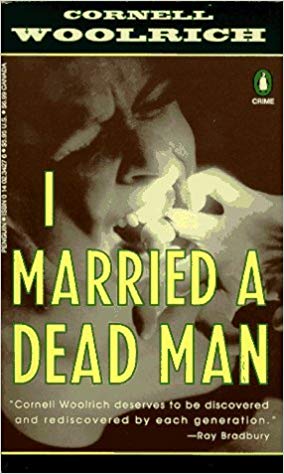

I Married a Dead Man by Cornell Woolrich

Tags: crime-fiction,

I can’t believe I’ve gone this long without discovering Cornell Woolrich. I had heard of him, but I had never read his work until now. The blurb on the cover of the book compares Woolrich to Raymond Chandler. I would actually say he’s quite a bit deeper and more nuanced. While Chandler focuses on the social world, Woolrich focuses much more tightly on the interior world of his main character.

In fact, he gets the reader to identify so closely with Helen/Patrice in this book, I had to reopen it the day after I’d finished it because I couldn’t remember if it was written in first person or third. It’s third-person, but it’s so powerfully colored by the protagonist’s thoughts and perspective that it’s easy to misremember as a first-person narrative.

Woolrich is a brilliant writer. That much comes out clearly in the prologue, which is among the best openings of any book I’ve ever read. It’s telling too that there’s no action in this section. The narrator merely gives a brief overview of her current life. (The prologue and epilogue are the only sections of the book written in first-person.) She lives in a beautiful house in a peaceful town, she loves her husband and son, and yet she and her husband are haunted by something that happened in the past and can find no peace.

That’s it. No explosion, no crash, no dramatic killing. And yet it’s utterly enthralling. The character has drawn you so fully into her confidence, her perspective is so rich and her language is so strangely powerful, you have to read on.

The rich description carries through into the third-person narrative that begins with chapter one. Here’s the main character, pregnant and abandoned on the first page of chapter one:

She was about nineteen. A dreary, hopeless nineteen, not a bright, shiny one. Her features were small and well-turned, but there was something too pinched about her face, too wan about her coloring, too thin about her cheeks. Beauty was there, implicit, ready to reclaim her face if it was given a chance, but something had beaten it back, was keeping it hovering at a distance, unable to alight in its intended realization…

Her head was down a little, as though she were tired of carrying it up straight. Or as though invisible blows had lowered it one by one.

You rarely see that quality of writing in crime fiction, in part because crime fiction tends not to focus on sensitive people. The quality of writing is consistent throughout the book. Here’s a snippet from a later scene. It’s autumn, and Patrice, still hopeful and determined after taking many more blows, is returning from a funeral.

The leaves were brightly dying. The misty black of her veil dimmed their apoplectic spasms of scarlet and orange and ochre, tempered them to a more bearable hue in the fiery sunset, as the funeral limousine coursed at stately speed homeward through the countryside.

The writer uses a number of interesting devices to brilliant effect. For example, one very short chapter near the middle of the book appears three times in a row. It’s simply a description of what the main character sees when she looks out her window in the morning. In the first version of the chapter, the description is bright and full of hope. In the second, it’s bittersweet, weighted down with a sense of impending loss. In the third, it’s dark, heavy, and threatening.

In three pages, that simple device portrays the decline in Patrice’s mental and emotional state more powerfully than thirty pages of nuanced description could ever do. For all the richness of his writing, Woolrich doesn’t waste any time conveying what he needs to convey.

Woolrich explores some of the same psychological territory as Jim Thomson, though he comes at it from the opposite direction. Thompson often begins with some petty criminal committing a petty act and then delves into the mind of his disturbed main character as he moves toward some violent and catastrophic explosion. Thompson’s main character is always male and is usually the perpetrator. Woolrich begins in his character’s mind, his character is a woman, and she’s the victim. Thompson’s writing is dark and powerful because of its spare, raw directness. Woolrich’s power comes from the richness and elegance of the language, of the perspective, and of the world he paints. While he does focus mostly on his characters' interior, he paints just as rich a portrait of the social world as Chandler.

This book is primarily a psychological suspense: a slow, weighty, and relentless act of brutality against the psyche of a good and honest and vulnerable person. It portrays the effects of evil much more powerfully than so much of today’s crime fiction, which simply focuses on acts of physical violence.

If you read the prolog, you’ll know at once if the book is for you. And if you like this one, check out Dorothy Hughes' In a Lonely Place .