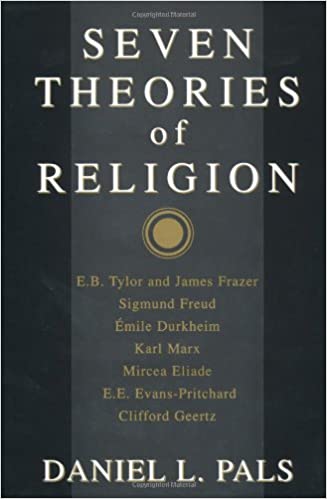

Seven Theories of Religion

Tags: religion, non-fiction,

Daniel L. Pals Seven Theories of Religion describes seven different attempts to describe what religion is, how it arose, and what it means to society. The book begins with a look at the two writers who first attempted to study religion through a scientific lens: E.B. Tylor and James Frazer. Both men described what they perceived as the evolution of religion across numerous societies around the world.

They each described essentially the same progress, from primitive magic to animism (where everything in the world was inhabited by some spirit) to polytheism to monotheism. Each step represented an evolutionary advance, with each new religion superior to the one that preceded it.

These two theorists used methods that are now considered scientifically unsound, basing their theories entirely on secondhand reports of “primitive” cultures that they took at face value. While their conclusions have been rejected, their work in gathering field reports from around the world and exposing universal patterns in religious belief and practice became invaluable to later generations of psychologists, sociologists and anthropologists. Frazer’s The Golden Bough in particular, while flawed, represents a monumental effort of research, scholarship and synthesis.

After Tylor and Frazer’s attempt to outline a worldwide history of religious thought, Sigmund Freud, Karl Marx and Emile Durkheim took “the science of religion” in another direction. Each was more concerned with the function of religion in the life of the individual and in the context of the broader society.

Durkheim’s interpretation of religion’s role is the most charitable of the three. He sees the religious rituals in which the entire community participates as a form of social glue, reinforcing social bonds and reaffirming shared values. In Durkheim’s view, the “god” of all religions is society itself, which is the life-giving entity to which all contribute and from which all benefit. The individual cannot live without the protection and cooperation of his neighbors. Religious belief states this in its moral and ethical codes, and ritual reminds the individuals of their place in the community. Religion’s function is ultimately to reinforce social structures.

Marx’s view is much simpler. Religion, he famously said, is the opiate of the masses. It’s a delusion that serves the ruling classes by convincing the powerless not to seek their due in this life, but to accept instead that they will be rewarded after death, when the game is over. It’s a pernicious delusion the perpetuates social inequality and unnecessary suffering.

And that’s about all he has to say. For Marx, no topic is worth thinking about except as it relates to class and economic struggle, and if he can dismiss a subject as monumental as religion in a sentence as concise as that, so much the better, for then he can return to flogging his favorite bogeyman, the capitalist.

Many critics have pointed out that religion exists in all human societies, and that Marx’s criticism doesn’t address its significance in cultures that do not exhibit the crushing economic inequalities of nineteenth century industrial Europe. Marx has nothing to say to this, and though there is some truth to his assertion that religion is used a tool to quell dissent and maintain the power of the ruling classes, that’s as far as his dismissive view can take us.

Of all the views presented in Pals' book, Freud’s stands out the most, and not because of the insight it provides about religion, but because of the insight it gives us into the man. Freud was openly hostile to religion, which he saw as a useless remnant of humanity’s ignorant and superstitious past.

Freud examines the Judeo-Christian religion and finds it to be just another manifestation of the Oedipus Complex. It is, in fact, “the universal human neurosis.”

While the personal Oedipus Complex involves a little boy’s desire to kill his daddy so he can screw his mommy, religion is the social Oedipus Complex that stems from an event in the distant prehistory of the human race, when the sons of the tribal chief rose up and killed Big Daddy so they could take over. Chaos ensued, and then the sons all agreed that killing Big Daddy–as much as they wanted to do it–was a bad idea, and from now on, they should worship him instead.

Freud gives no evidence of the historical event of Big Daddy’s murder. He merely posits it as a fact so he can insert his Oedipus Complex into the story and have it neatly explain everything.

Freud was an exceptionally gifted writer. You’ll see that especially in his case studies, which are striking, insightful, and fascinating. Even among the best writers, very few express ideas with such clarity, force and depth of perception.

But his ideas are tainted by an obsessive focus on sexuality–and a perverse kind of sexuality at that–as well as an obsessive concern for his reputation and his legacy. I sometimes think the man wanted to be a cult leader. Maybe he was.

In his memoirs, Carl Jung describes the meeting with Freud that led to their break. While Freud insisted that everything in the subconscious mind could be explained by sexual desires (and primarily by taboo sexual desires), Jung insisted that there was much more going on in human life, and that the symbols of religion and mythology best captured the powerful irrational knowledge that reason and logic could never fully express.

Please, Freud said (and I’m paraphrasing here), don’t drag us back into the muck of religion and superstition.

In Jung’s description of the encounter, there was almost a desperation in Freud’s plea, like he knew this was the one thing that could undo him and his reputation and his cult: a deeper and broader truth, shapeless, darker, harder to pin down.

Freud was held in high esteem by his colleagues and disciples because he had “nailed it.” He had reduced all of human psychology to a single story. This trend toward reductionism was a hallmark of nineteenth and early twentieth century science. Marx and Freud and many others believed that scientific study could lead us to a single theory that explained everything in society in the same way that the study of physics and chemistry exposed the immutable and universally applicable laws of atoms and molecules. If the story of psychology turned out to be more complex that Freud proclaimed, if he hadn’t actually nailed it, where would his reputation be then?

If you’re a thinking person, or if you’re not a man, you’ll see one glaring hole in Freud’s Oedipal theory right up front: it says nothing about girls or women. What motive would they have to kill daddy and get in bed with mommy?

Freud has a convenient explanation for that. Girls are just boys who had the terrible misfortune of being born without a penis, so they spend their whole lives longing for one.

So, already this guy has a faulty understanding of one half of the human race and no understanding of the other. Now he’s going to try to explain the infinitely complex phenomenon of religion. And of course, in doing so, he turns to his trusty explanation of everything else in human nature: kill daddy, screw mommy.

There’s a saying that, to a man whose only tool is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. This is Freud.

Again, he’s a brilliant writer and a brilliant man. His examinations of individual patients are insightful, nuanced and extraordinarily well expressed. The conclusions he draws from his observations, however, show a mental block, a personal hangup that likely describes his own psychology, and that he unknowingly projects onto others. Maybe Freud himself had an Oedipus Complex. That doesn’t mean everyone else does.

Like Marx, whose monomaniacal obsession was economic inequality, Freud’s conclusions contributed less to posterity than his methods. Freud asked questions and listened, and lo and behold, he learned from his patients! (This is a lesson many doctors still haven’t taken to heart.)

Likewise, Marx looked at all social structures, practices, and beliefs in terms of how they represented and reinforced the values of the ruling class. Both he and Freud provided the twentieth century with new methods of inquiry that opened up new models of understanding. If they were unable to apply broad and expansive interpretations to the world they studied, that was likely due to peculiarities of their own psychologies.

Near the end of his life, the satirist Jonathan Swift said that a single experience in his boyhood provided the pattern for all of his later experience. While fishing on a river, he caught a big one. He could see the fish beneath the water as he hauled it in, but when it got to the surface, it dropped off the hook and swam away.

This is the pattern in Swift’s satire: high hopes dashed time and again by cruel reality. Reading Freud, I get the sense that his formative experience was getting turned on while nursing at mommy’s breast. He then spent the rest of his life trying to explain away a painful case of infantile blue balls. Meanwhile, eight-year-old Karl–savagely ill-tempered and without a nickel in his pocket–was the only kid on the block to end up empty-handed after the ice cream truck drove by. And by God, the world was going to pay for that injustice, to the tune of twenty million Soviet lives!

After discussing the reductionist views of religion espoused by Durkheim, Marx and Freud, Daniel Pals turns his attention to the richer examinations carried out by Mircea Eliade, E.E. Evans-Pritchard and Clifford Geertz. All three spent considerable time living in societies outside the West, and all believe that you cannot come to any theory of religion without understanding how it is experienced by those who believe in and practice it.

Needless to say, these three provide deeper, more nuanced and sympathetic portraits of what they set out to study. While Eliade aims at a comparative view of various belief systems, Evans-Pritchard and Geertz, both anthropologists, spent years living among the subjects of their studies to produce richly detailed ethnographies.

Regarding the approach these last three took, Pals makes a passing comment that deserves elaboration. The anthropologists, he points out, recognized that the mistake of the reductionist thinkers was to try to explain religion from the outside. That’s like a person trying to explain a book without any understanding any of the words it contains.

This is an excellent metaphor. Let’s run with it and do a little thought experiment. Let’s say Karl Marx was illiterate. Everywhere he goes–the park, the train station, the coffee shop–he sees people opening books, staring into them for hours as if paralyzed and entranced. Occasionally they laugh or cry, or knit their brows in consternation.

“What’s going on?” he wonders. “It’s as if some drug has taken possession of them. And they do this willingly! The books don’t force themselves into people’s hands. People seek them out, open them on purpose, hold them in front of their faces, become blind and insensitive to the world around them, and sink into an opiated stupor.”

“Yes,” says Freud, “I’ve noticed it too. It’s a universal neurosis. They treat these fetishistic objects as if there’s something of value inside.”

“The race will never be free,” says Marx, “until we rid them of this scourge!”

“Indeed,” says Freud. “It’s our duty to enrich humanity by eradicating this superstitious fetish.”

Marx: “Right. And the only path to our goal is violence. Who shall we kill first?”

Freud: “Daddy.”

Sylvia Plath: “Count me in!”