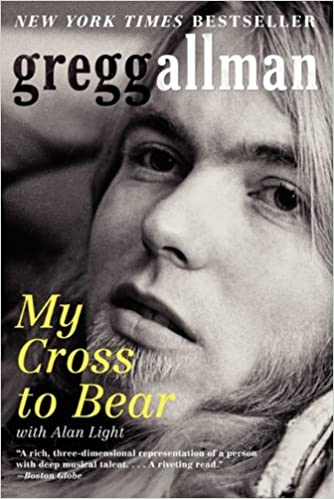

My Cross to Bear by Gregg Allman

Tags: non-fiction, memoir,

Gregg Allman’s memoir, My Cross to Bear, covers a lot of ground, from the murder of his father to the musician’s coming to terms with his own fatherhood late in life. Gregg and his older brother, Duane, were born in Nashville and raised by a single mom who could barely keep the family afloat.

The brothers were sent off to military school at a young age–Gregg was only eight–to avoid being sent to the orphanage. As you can imagine, this wasn’t a good fit for two creative types who didn’t yet know they were bound to be musicians. Allman, however, credits the discipline instilled there, and the beatings he took, bitter as they were, for toughening him up later in life.

He also notes the eye-opening lesson of his and Duane’s escape from the place. During high school, when he’d had enough, older brother Duane simply walked out and never looked back. Gregg soon followed, surprised to learn that the seemingly inescapable life of misery in which he felt trapped depended on his consent to remain there, a consent which he could simply revoke.

The brothers went back to live with their struggling mother in Daytona Beach. One day, Gregg was watching an older neighbor, a guy in his teens or early twenties, paint his car black. The car was already black, Allman noted, and the guy was painting it with house paint–bumpers, headlights, wheels and all. He knew the neighbor had some developmental disabilities, but still he watched, fascinated by the kid’s strange behavior.

The two got to talking, and Allman asked the neighbor about an old guitar sitting on the porch. The neighbor picked it up and strummed out a few tunes. Allman was captivated.

He got a paper route and saved up enough to buy his first guitar, a twenty-one-dollar finger-bleeder from Sears. He was actually a dollar short, and his mom gave him the last buck so he could buy it. He mentions later in the book that his mom told the brothers at an early age, “I don’t care what you choose to do in life, but strive to be the best at it.”

Allman started teaching himself guitar, and then showed his brother Duane what he had learned. Duane, the more forceful of the two personalities, took the guitar and started teaching himself.

The relationship between the brothers is probably the formative relationship Gregg’s life. Although they were just a year apart, Duane was the dominant figure throughout his short life.

The two often fought, as brothers do, and always forgave each other, as brothers will. To get an idea of how rough and raw life was in those days, especially for the poor in the South, Allman relates the tale of one particularly bad fight between him and Duane when they were kids climbing a tree.

Gregg stepped on Duane’s shoulder, popping a painful blister. Duane was so mad, he went into the house, got a rope, tied a noose, and put it around Gregg’s neck. By chance, their mother came out to the yard just then to find young Gregg unable to breathe.

She took the noose off his neck and said to Duane, “What do you mean, hanging your brother like that? Get in the house!” And she gave him a whoopin.

After buying and listening to every record they could get their hands on, and practicing in every spare moment of time, the brothers started playing covers for anyone who would listen. Gregg, who was shy, noted that for the first time in his life, the girls paid attention to him.

The tale of the next few years is one of dedication. The brothers played every chance they could, at any venue, for any audience, anywhere. Malcolm Gladwell popularized the idea of the ten-thousand-hour rule, which says that mastery in any field of work requires ten thousand hours of practice.

Gladwell cited the Beatles as an example. The band used to play something like twenty gigs a week at a small club in Germany, honing and tightening their skills in front of audiences of drunks while making just enough money to feed themselves.

Before they hit the radio and the big time, they had already put in ten thousand hours of practice together, according to Gladwell, and so had attained a level of mastery well above that of other young bands.

While ten thousand hours of work is enough to develop skill, I would argue– and I think Gregg Allman would too–that passion is the driving factor behind genius. You can put in ten thousand hours, but how much of you actually shows up in those hours?

For the Allman Brothers, it was one-hundred percent. They were in it heart and soul, no matter how depressing the turnout at some of their early shows might have been.

Allman, who I think was one of the most powerful singers of his generation, admits that he became the band’s singer in high school by default, because no one else wanted to be the vocalist. He says he didn’t have much natural talent when he started, but he had a tremendous desire to learn. He was deeply tuned into the way other singers could move an audience, and in addition to studying them, he asked them outright about technique.

He learned early on that he had to push past his stage fright, doubt, and self-consciousness.

To sing properly, you have to get into a mind-set where you don’t give a damn if somebody doesn’t like it. You couldn’t care less, you’re singing for the gods… You’re putting your whole soul into it, all the happiness you ever had, every tear you’ve ever shed–all of that goes into your singing.

This is the same attitude Ray Charles developed early in his career, when he played to crowds that were sometimes hostile, sometimes indifferent, sometimes racist. He and Quincy Jones used to repeat a mantra: “No part of my self-worth depends on your opinion of me.”

It takes a lot of struggle and a lot of faith to live those words.

While Gregg was convinced they could never make a life of what they were doing, Duane was even more convinced they could. The older brother’s confidence eclipsed the younger brother’s doubt every time, and forward they went.

The bulk of the book concerns the band’s early brotherhood and sense of destiny, its rise and fall with the deaths of Duane and Berry Oakley, followed by its resurrection and the wild life on the road.

The creative life is not one of stability, especially when it unfolds amid drug-fueled crowds of swooning youth in the era of free sex. Gregg Allman had one hell of a ride, and the ups and downs took their toll.

As much as his fans adored him, and as much as the women threw themselves at him, Allman confesses he was lonely and wanted the stability of a good, close friend. His marriages, he said, were attempts to hold on to valuable friendships, and they never worked out.

Allman had no model of stability in his life, and his work kept him on the road for months at a time. He was a heavy drinker and a heavy drug user, and so were most of his wives. This is not a recipe for success. And if you think you’ve lived through or heard about some messed up marriages, wait till you read about him finding his wife in bed with his friend, and fallout of that particular incident.

“After about my fifth wife,” Allmans says, “I realized that maybe I shouldn’t be married.”

The strongest thread running through Allman’s life, right alongside his music, is his struggle with addiction. He used cocaine, heroin, weed, and every pill he could get his hands on. Drugs provided a way to regulate his moods and energies, amping him up to go on stage, and then bringing him back down afterwards so he could sleep.

His unprocessed grief over the deaths of his brother and Berry Oakley, combined with the instability of the road life and his devotion to an emotionally intensive art form, fueled addictions that eventually resolved into alcoholism. By the nineteen nineties, he drank so heavily, he could barely function. He kept a half-pint under his bed as he slept, because if his drunkenness wore off in the middle of the night, he’d wake up shaking and sweating.

For someone drinking a liter or more of liquor a day, he notes, alcohol withdrawal is every bit as bad as heroin withdrawal. He knew the drink was ruining his music and his life, but still he couldn’t stop.

Traditional rehabs didn’t work for him, and neither did Alcoholics Anonymous.

I only went to AA once… I walked in, and these three girls dragged me in the corner and asked me if I’d sign this and that. One of them was hitting on me pretty heavy. I looked at them and said, “Anonymous, my ass.” I walked down the street and got drunk.

Waylon Jennings later confided to him that he and Johnny Cash had the same problem. “Me and Johnny, we can’t go to the AA meetings, or to NA meetings either. But I’m gonna tell ya, brother, all you need to have an AA meeting is two drunks and a coffee pot, and that big book.”

Allman finally kicked the drinking and the drugs–and cigarettes to boot–by hiring two nurses to watch over him in his own home, twenty-four-seven, for several weeks. No one was going to kick his habit but him. “[T]he one it started with was me; a person has to want to be set free from that shit.”

Near the end of the book, Allman notes that his mother, who had a very difficult life, was also a heavy drinker. She had to take the edge off somehow, and she had no other retreat. But she too quit. As she put it, “I drank till I didn’t want to drink no more, then I stopped.” She lived well into her nineties, still active and fit.

Near the end of a very eventful life, Allman reflects on how individual our paths are, how no one can walk our path for us, and how, as hard as the road my be, redemption is open to all who sincerely seek it. “There are as many ways to write a song as there are songs, and there are as many ways for people to get healed as there are diseases.”