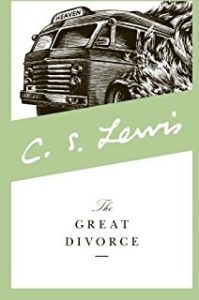

The Great Divorce – C.S. Lewis

Tags: general-fiction,

C.S. Lewis’ allegory opens with the narrator, presumably a middle-aged Englishman, walking through the rainy streets of a city at dusk. He happens upon a line of bickering people waiting for a bus and, almost by accident, he’s in the queue, and then aboard the bus, not knowing where it’s bound.

As the bus ascends, he gets a broad view of his vast, gloomy country, with its houses spread miles apart as its inhabitants try to distance themselves ever further from their neighbors.

The bus eventually rises to a lush, sunlit country in which the substance of all things, from the grass to the water to the animals, is so hard and weighty that the passengers on the bus are mere ghosts by comparison.

Bright spirits approach the passengers one by one, each assigned to a specific individual, and try to convince the ghosts to accompany them on the difficult journey over the mountains to a land of joy and love. The one condition is that they can’t take anything with them.

One by one, the ghosts refuse. The proud ones cannot give up their important roles in the world below. The wounded and the wronged cling to their wounds as an identity that defines their entire being. The ones who exercised power refuse to go forward without the guarantee that their power will be preserved or restored.

The bright spirits cannot give the ghosts a sense of the joy that awaits them because the ghosts are so attached to their own misery that they can’t conceive of joy. Unaware of the limits of their understanding, the ghosts cling to their identities as a last possession, and fear that once they’re stripped of that, they’ll become nothing.

The spirits argue, to no avail, that once the ghosts relinquish those last vestiges of self, they actually become more substantial, and the journey over the mountains becomes easier, though they acknowledge that the beginning of the journey is always painful, in different ways for different people. One ghost, a woman who was admired and beautiful in the world below, cannot bear the shame of being transparent, of being “seen through” in this new world. The spirit explains that surrendering to her shame is the first step toward becoming a more substantial being.

“Don’t you remember on earth–there were things too hot to touch with your finger but you could drink them all right? Shame is like that. If you will accept it–if you will drink the cup to the bottom–you will find it very nourishing: but try to do anything else with it and it scalds.”

The ghosts are more interested in complaining about their place in the world below than in listening to what awaits in the world above. One of Spirits, offering joy and freedom to an unreceptive ghost, expresses his frustration: “Friend,” said the Spirit, “Could you, only for a moment, fix your mind on something not yourself?”

The story is in some ways like an abridged and inverted version of Dante’s Inferno. The setting is heaven instead of hell, and instead of seeing the punishment inflicted on the damned, we see the mindsets and attitudes that lead to their misery. None of these ghosts did anything particularly horrible. They look like our neighbors, our families, and ourselves. They’re manipulative or sulking or spiteful or proud. They’re selfish and inflexible. They lack empathy. They’re full of petty grievances, and their smothering “love” for others is merely a desire to possess and control.

Many of them sunk unwittingly into misery, like the grumbling old woman, whose downward trajectory through life is described thus:

“…it begins with a grumbling mood, and yourself still distinct from it: perhaps criticizing it. And yourself, in a dark hour, may will that mood, embrace it. Ye can repent and come out of it again. But there may come a day when you can do that no longer. Then there will be no you left to criticize the mood, nor even to enjoy it, but just the grumble itself going on forever.”

Others have followed a similar descent, so slow and subtle they can’t recognize their own misery. One of the Spirits describes an example:

“The sensualist, I’ll allow ye, begins by pursuing a real pleasure, though a small one… But the time comes on when, though the pleasure becomes less and less and the craving fiercer and fiercer, and though he knows that joy can never come that way, yet he prefers to joy the mere fondling of unappeasable lust and would not have it taken from him.”

The narrator watches as, one by one, the ghosts refuse the offer of joy and board the bus back to hell. And here again Lewis inverts Dante. In The Inferno, the souls know they’re suffering, their suffering is inflicted from without by a being substantially greater than them (the devil) against whom they are powerless. Hell has no exit, and their suffering is eternal.

In The Great Divorce, the inhabitants of the underworld are free to go anytime. They can and do board that bus to heaven, but they choose again and again to return to gloomy world below, to the role and the self and the life they’ve so identified with that they cannot let it go. Their hardships and troubles are self-inflicted, and they don’t know they’re suffering.

“There is always something they insist on keeping even at the price of misery,” one of the Spirits remarks. “There is always something they prefer to joy.”

Unlike the exotic world of extreme torture that Dante paints, Lewis’ hell looks a lot like the world we live in now.