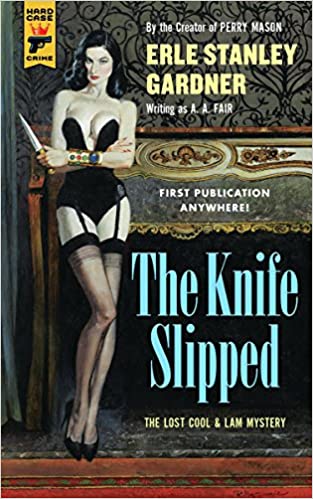

The Knife Slipped

Tags: crime-fiction, detective-fiction,

This is the first I’ve read from Gardner, and it’s a good one. It’s more of a straight-up detective mystery than a noir, and it doesn’t attempt the reach the depth or weight you find in the best crime and noir novels, but it is entertaining.

Bertha Cool is the unapologetically unorthodox head of the B. Cool detective agency. Donald Lam, “the runt,” is her new, wet-behind-the-ears junior detective. He’s got plenty of brains and more than enough street smarts to do his job, but he has a weakness for women in trouble, or perhaps for any woman who will give him the time of day. As Bertha puts it, “You pick some little tart and fall in love with her every time.”

Unlike Lam, Bertha Cool has no patience for sentiment. She’s big, fat, greedy, strong, smart, clear-eyed, determined, and will have everything her way. The two of them make quite a team. Gardner apparently published 29 novels about this pair, and they seem interesting enough to follow through a number of adventures.

This particular volume, which brings the series total to 30, was the second. Written in 1939, it was not published until 2016. I think Bertha Cool was much of the reason the original publisher refused to print it. Readers of mass market genre fiction are supposed to like the protagonists. Bertha Cool was too strong a character for readers in 1939 to stomach. Gardner could have made her more palatable to his Depression-era audience by making her slim and pretty and somewhat vulnerable, but she’s too strong and clear-sighted to be put in a weak body, or to be saddled with the need to be needed. She’s glad her husband is dead, glad to make a living on her own, and never content to conform to expectations of what a woman should be.

Cool and Lam are pursuing an adultery case in this book. At least in the beginning. It turns into more, but I won’t spoil it. Gardner’s treatment of adultery, and of sexuality in general, is as factual, clear-eyed and realistic as Bertha herself. Both Bertha and Donald Lam recognize desire as an inescapable element of human existence, which is not to be shunned or neglected or too brutally suppressed. Bertha even admits early on that she engineered some of her late husband’s affairs, steering him toward less destructive women, in order to preserve the peace of their union.

That sort of talk just wouldn’t go over well in 1939. Nor would Lam’s very reasonable attempts to convince the guilt-ridden Ruth Marr that her desire is normal, and that acting on that desire (the source of her shame) is normal too. The mystery/thriller genre in general tends to be moralistic. Readers expect a protagonist they can root for, and a villain they can root against, and they expect the good guy to win in the end.

But Gardner goes muddling with convention by having his good-guy detective tell Ruth Marr she’s not a slut, and by having the fat, bossy, opinionated, unfeminine Bertha Cool push around every man she encounters. It must have added up to more than his editors could take. Worst of all, unlike the traditional bad guys who are supposed to get their comeuppance in this moralistic genre, Bertha Cool turns out to be consistently right in her cynical assessments of just about everyone.

The plot meanders a bit in the second half, as many mysteries do, but it’s a good read overall.