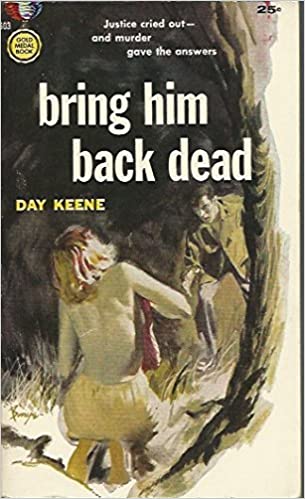

Bring Him Back Dead by Day Keene

Tags: crime-fiction,

In the opening of Day Keene’s Bring Him Back Dead, sheriff’s deputy Andy Latour seems to be stuck in the wrong job and the wrong marriage. His wife, Olga, a descendant of the faded Russian aristocracy, barely speaks to him. He had promised her a life of wealth and ease as the oil boom struck southern Louisiana and the Delta Oil Company had opened a test well on his land.

But the well didn’t pan out. Latour couldn’t deliver on his grand promises, and had to settle for a $250-a-month deputy job in his once-sleepy hometown of French Bayou. After the discovery of oil in the parish, and in the nearby Gulf, the town is awash in money. The roughnecks working on the offshore rigs like to drink and party when they’re off the clock, and the town’s main street has become a carnival of swindlers, drunks, prostitutes and brawlers. The sheriff and his deputies, unable to control the mayhem, find it’s more profitable to let it all happen. Their generous share of the oil boom money comes from turning a blind eye to whoever pays them off.

Keene writes a brilliant description of how the rush of easy money has corrupted a once-decent town:

French Bayou had changed. The discovery of oil in the Gulf had seduced her. She was no longer a genteel Creole lady dozing in the sun. With the oil-company-built jetties forming a pair of splayed white legs and bar-lined Lafitte Street her torso, she looked more like a big-eyed back-country girl lying flat on her back in the reeds, willing and eager to take on all comers, delighted by this endless source of revenue she’d discovered in her own body.

The main character, Andy Latour, is a straight arrow, and he’s seemingly the only one the money has passed by. His land was barren of oil, and he won’t take a bribe from anyone, though he gets plenty of offers. Many of the residents resent him for enforcing the law. Even the other deputies resent him because his honesty and integrity make them look all the more crooked by comparison.

Within minutes of being introduced, Latour’s life goes from bad to worse. As soon as he steps out of his house, someone takes a shot him. He gets up from the ground to find a bullet hole through his Stetson. Before the day is out, he’ll survive three more shots.

When Latour mentions the assassination attempt to a fellow deputy, the deputy shrugs it off, reminding Latour that he’s locked up a lot of punks that the other cops would have let off with a bribe. He’s sent some rough men to Louisiana’s notorious Angola prison as well. If someone has it out for Latour, it’s his own fault.

After a second attempt on his life later in the day, Latour realizes that whoever is after him is determined, and wants him dead as soon as possible. This isn’t just some punk looking for revenge. This is someone with a bigger motive. But who? And what’s the motive?

Unable to get a clean, witness-free kill, Latour’s assailant seizes an opportunity to frame him for a truly horrendous crime. Latour finds himself alone in the jail’s maximum security unit contemplating a mountain of seemingly incontrovertible evidence that pegs him as both a rapist and murderer. His colleagues doubt him, his wife doubts him, the whole town wants to lynch him, and his tone-deaf lawyer argues his case in a way that only makes everyone hate him more.

How’s he going to get out of this one?

You’ll have to read it to find out. This is good old-fashioned 1950s pulp. The author doesn’t try to get fancy. He just sets up a good story and has the sense to tell it straight.

One aspect of the story, however, does stand out from the general pulp/crime tradition. In the course of figuring out who has it out for him, Latour has to re-evaluate his life and all of his relationships, trying to understand who’s really on his side and who’s not. This results in a startling shift in perspective and a huge leap forward in Latour’s understanding of himself.

The sheriff’s department has to do some soul-searching as well. The brutal crime for which Latour has been framed draws heavy attention from the media, and the reporters expose French Bayou’s lawlessness in a way that would humiliate any cop. The brutal crime of which Latour is accused becomes an existential crisis for the town, forcing everyone to ask themselves which side they’re really on, and what kind of person they truly want to be.

One reason I enjoy mid-century American pulp fiction is because it goes straight past the varnish of society to the animal roots of human behavior. It’s about sex, violence, survival, and death–the fundamental realities of animal existence. All of civilization is a buffer against the rawness of those realities, and in genteel high-brow literature, the buffer is so thick we can’t get to the fundaments underneath. (Henry James, anyone?)

Pulp fiction deals with many of the same themes as Greek tragedy and Shakespearean drama, which, in their day, were also popular forms aimed at a mass audience. In fact, if you think pulp fiction is lurid, try re-reading Oedipus Rex or Hamlet.

Keene, like most fifties pulp writers, doesn’t waste words. A good, raw story is best told in plain language. There’s an art to that, an art to the writer getting out of the way of a good story, though readers raised on florid prose and overwrought metaphor can’t or won’t see this. If literary fiction is French cuisine, with all its artful sauces, pulp fiction is Italian cooking, with the chef standing back to let the fresh ingredients speak for themselves.