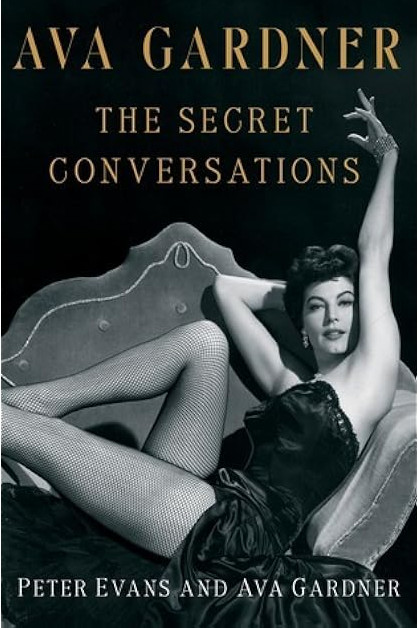

Ava Gardner, The Secret Conversations

Tags: biography, memoir, non-fiction,

Ava Gardner, The Secret Conversations, is a book about a writer trying to write a book about Ava Gardner. In 1988, Gardner was recovering from a pair of strokes that had left her with a limp and immobilized one side of her face. She was sixty-five years old, nearly broke, and living as a recluse in her London apartment. The damage from her strokes had ended her acting career, and it looked like her last shot at earning money was to write a memoir.

Peter Evans, a veteran London journalist, was assigned to be her ghostwriter. This book chronicles Evans’ many intimate conversations with the actress. By then, Gardner was an alcoholic suffering the ill effects of decades of heavy smoking.

She relates, by the way, that the day she arrived in Hollywood, she caught a glimpse on the MGM lot of Lana Turner taking a smoke break outside a set where she’d been filming. Turner withdrew a long cigarette from an elegant gold case, lit it with a matching gold lighter and blew out a long stream of smoke.

Gardner, a shy eighteen-year-old country girl from Grabtown, North Carolina who felt out of her league among the glamorous movie stars, thought it was the most elegant thing she’d ever seen. With the pocket money the studio have given her, she went out and bought the same cigarette case and lighter, hoping to match Turner’s elegance and sophistication. Looking back on that day nearly fifty years later, she said taking up smoking was the worst mistake she ever made.

To be fair, she made the same comment about at least one of her three marriages, but the story of how she took up smoking is the story of her early Hollywood years in microcosm: the country girl out of her element, trying to live up to impossible expectations.

Gardner grew up poor, on a farm, with a humble but close-knit family. She was a tomboy, and the baby of the family, several years younger than her nearest sister. She never acted or sang, and at age eighteen had enrolled in secretarial school in rural North Carolina and was learning to type.

Her sister had married a photographer and moved to New York. When Gardner visited, her sister’s husband took a photo of her, which came out well. He hung it in the window of his Manhattan photo studio as an example of his work.

A young man who happened to be a junior clerk for MGM’s parent company was smitten by the photo. He entered the photo studio and asked for her phone number, which Gardner’s brother in law refused to give. The clerk lied and said he was a talent scout for MGM and Gardner should get in touch with him.

Gardner, back in North Carolina, said go ahead and give him my info. Her brother-in-law tried to track down the clerk at MGM but couldn’t. Because the clerk had lied and said he was a talent scout, the photographer sent Gardner’s photo to MGM’s scouting department along with a note.

The scouts at MGM were puzzled. They hadn’t asked for a photo, and they had no idea who the subject was, but they liked the way she looked, so they called her in for a screen test. Gardner took the train from North Carolina to New York and did the test in her one good country dress. Then she went back home and forgot about it.

She was really struggling at the time. Her father had recently died, and now her mother was terminally ill with cancer. Gardner was eighteen and didn’t have a job.

A few months after the screen test, when she had practically forgotten about it, she received a letter from MGM saying they wanted to sign her to a seven year contract. She and her sister took a train across the country to Los Angeles. When they arrived, they were given a tour of the MGM lot. The first person Gardner met on the lot was Mickey Rooney, who at the time was the biggest star in Hollywood. Rooney, two years older, was instantly attracted to her. He called her that night, and within months, they were married.

How’s that for an improbable turn of fate? How could any eighteen-year-old adapt to so much change, so quickly?

The studio started her off with bit parts. They trained her how to dress, how to stand, how to speak. They gave her speech lessons to get rid of her thick North Carolina accent. The country girl with the drawl who liked go barefoot and climb trees became the stylish, sophisticated socialite dressed to the nines. She was going out nightly to the clubs, the fights, the races with the people she had grown up idolizing on screen.

Gardner was a virgin when she married Mickey Rooney, who was notoriously horny and unfaithful. The marriage last only about a year, but it helped Gardner grow up fast.

After splitting with Rooney, Gardner had an affair with Howard Hughes and then married musician Artie Shaw. Shaw was an intellectual, the antithesis of Mickey Rooney. He was also cruel. That marriage lasted a year.

When Gardner started seeing Frank Sinatra, his career was in decline, and hers was ascendant. She was finally getting leading roles, seeing box office success and gaining critical praise. Meanwhile, both MGM studios and CBS records had dumped Sinatra, and his fans, as Gardner put it, were “finding someone new to throw their panties at.”

This isn’t a good recipe for the start of an affair. Sinatra’s ego was fragile, and he was always jealous of Gardner and her former lovers.

The two of them became grist for the gossip papers, hounded everywhere by the paparazzi. The harassment and lurid publicity was so bitter to them, they promised each other that neither would ever write a memoir.

This was the source of much of Gardner’s ambivalence in Evans’ book. Even as she pours out her heart to the reporter–and a beautiful heart it is–she keeps wanting to quit the whole project. The loves and friendships she talks about are too personal to be aired to a public whose prurience and judgment have stung her many times over the decades. Gardner is always on the fence about this project, always close to abandoning it even if it means giving up her last shot at a decent payday and dying in poverty.

Eventually, she does call it quits, which is hard for the reader, because there was so much more to tell.

This book is essentially a chronicle of the relationship between an extraordinary spirit who had lived an extraordinarily unlikely life and the reporter who tries to draw from her her story. The deeply private woman who has been burned by the press too many times is often reluctant to say anything, while the faded star who had lived her life in the limelight craves attention and knows how to keep it with her stories.

Gardner was an intensely attractive woman on screen. In person, her depth and honesty, her colorful insights and her genuine compassion make her even more attractive as a person. In relating their hours of conversation, Evans does a good job of conveying her color and warmth, her sharp tongue and mind, her combativeness and need, her pride and strength. As biographies go, it’s an odd, almost abortive attempt at a book, but it does convey its subject very well, and when it’s over, you miss her.