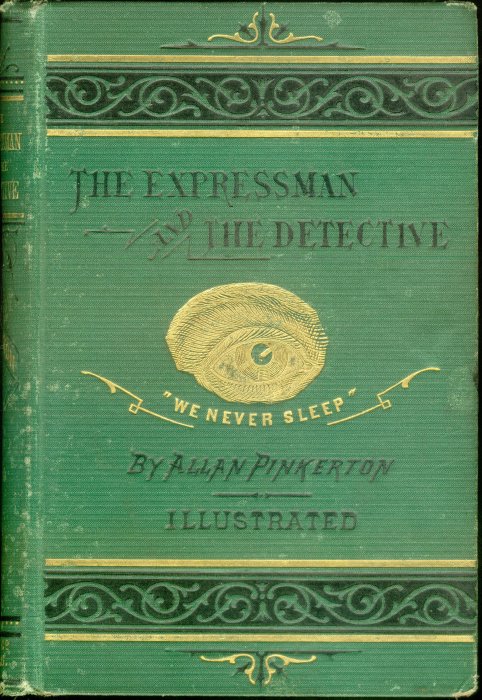

The Expressman and the Detective

Tags: non-fiction, true-crime,

The Expressman and the Detective, originally published in 1874, describes Allan Pinkerton’s 1859 investigation of a messenger suspected of stealing from the Adams Express Company in Montgomery, Alabama. Nathan Maroney had been an exemplary employee with a strong reputation, and there was no hard evidence against him, but the company’s Vice President suspected him of stealing a package containing $10,000.

After a lengthy investigation turned up nothing, Adams Express gave up and wrote the money off as a loss. A few months later, a package containing $40,000 went missing from the Montgomery station. The express company wrote to Allan Pinkerton of the North-West Police Agency in Chicago and asked him to investigate.

Some reader reviews on Amazon and Goodreads incorrectly assert that the book is fiction. It’s not. The New Orleans Times-Picayune ran a lengthy story of the trial as it concluded, in 1860, which was reprinted in a number of other US newspapers. The details of the Times-Picayune story generally agree with what’s in the book, though, obviously, the book goes into more detail.

Adams Express was so intent on making a public example of Maroney that they employed eight Pinkerton detectives round the clock for ten months to trap him. Maroney and his wife could not have imagined what a vast conspiracy surrounded them, or that nearly everyone they were interacting with was a spy sent either by Pinkerton or the express company. At one point, Adams Express agents throughout the South are sending letters to Maroney in New York, pretending to be the agent he dispatched to frame another man for the crime. By the end of the case, detectives had traveled over 50,000 miles to catch their man.

If you want to read the book, stop here because spoilers follow.

Allan Pinkerton, 40 years old at the time, had immigrated from Scotland at age 18. An ardent abolitionist, his Illinois home was a stop on the Underground Railway for escaped slaves heading north to Canada. His North-West Police Agency was a relatively small firm of private investigators, and this would be his first big case for a major company. He was passionate about his work and wanted to show the executives at Adams Express “that my profession, which had been dragged down by unprincipled adventurers until the term ‘detective’ was synonymous with rogue, was, when properly attended to and honestly conducted, one of the most useful and indispensable adjuncts to the preservation of the lives and property of the people.”

The Expressman and the Detective identifies the suspect at the outset, and then describes how a number of Pinkerton’s agents work together to uncover the evidence and bring him to justice. This makes the book one of the first, if not the first, police procedural.

Although Pinkerton believes Maroney is guilty, he knows he cannot secure a conviction unless he can catch Maroney with the money or get him to confess. Pinkerton employs two primary strategies to discover information: he assigns agents to shadow Maroney at all times, and he assigns other agents to befriend him and gain his confidence. Pinkerton believes that as the pressure of the investigation mounts, Maroney will have to talk to someone, and Pinkerton wants that someone to be his agent.

Early in the book, Pinkerton says:

I maintained, as a cardinal principle, that it is impossible for the human mind to retain a secret. All history proves that no one can hug a secret to his breast and live. Everyone must have a vent for his feelings. It is impossible to keep them always penned up.

This is especially noticeable in persons who have committed criminal acts. They always find it necessary to select someone in whom they can confide and to whom they can unburden themselves.

Pinkerton sends two agents to Montgomery: a German immigrant named Roch, who shadows Maroney wherever he goes, and a man named Porter who rents a room in the the boarding house where Maroney lives and slowly befriends him.

While the narrative of Maroney’s eventual undoing is suspenseful, the book is as much a historical document as a detective story, providing a rich portrait of the social world of the US in the 1850’s.

Although most people did not suspect how close the country was to war at that time, characters from both the North and South mention, in a very matter-of-fact way, how uncomfortable they are traveling in the other’s territory. The US appears almost as two separate countries in this book. Pinkerton doesn’t trust the legal system in the Southern states, or the one and only private detective in Montgomery. He won’t travel to Alabama to oversee the case because he fears he cannot keep his abolitionist views to himself.

When he sends Porter south to befriend Maroney, he gives specific instructions “to keep his own counsel, and, above all things, not let it become known that he was from the North, but to hail from Richmond, Va., thus securing for himself a good footing with the inhabitants.”

Agent Roch, who follows Maroney on long train journeys throughout the South, is able to escape notice by dressing as a poor German immigrant and traveling in the segregated car at the back of every train. Although Maroney suspects he is being followed, and is always on the lookout for the agent on his tail, poor immigrants and blacks were beneath the notice of Southern whites. Pinkerton understood that the moral blindness that permitted slavery was so profound that it had become almost a literal, physical blindness. There were certain people a Southern white man just didn’t see, even when they were right in front of him, day after day.

While Pinkerton draws attention to these prejudices, he also exposes some others that he doesn’t bother to look into. In any story, the unexamined assumptions and prejudices are the most powerful. In the initial investigation into the first theft–the one that Adams Express conducted before hiring Pinkerton–Maroney managed to convince the investigators of his innocence. But the Adams Vice President continued to suspect him because he discovered that in the distant past, Maroney’s wife had “led the life of a fast woman at Charleston, New Orleans, Augusta, Ga., and Mobile, at which latter place she met Maroney, and was supposed to have been married to him.”

While Pinkerton is generally careful to explain actions and clues that raise suspicion, he doesn’t bother explaining why a “tainted” woman is enough to taint a man. That belief is so deeply ingrained in the culture of his mid-nineteenth century readers that there’s no need to explain it to anyone.

The book always refers to Maroney’s wife as “Mrs. Maroney.” She doesn’t have a name of her own. According to James Horan’s The Pinkertons: The Detective Dynasty That Made History, her name was Belle, and her maiden name was Irvin. She was raised in a stable family in Philadelphia and ran off at a young age with a man who seduced and then abandoned her, leaving her to raise a daughter on her own. With no other options, she supported herself through prostitution before meeting Maroney. (At least, that’s what Pinkerton implies.) Maroney took Belle and her daughter to Montgomery, where he introduced Belle as a widow who had become his wife. The eight-year-old Flora, according to their story, was her child by her previous marriage.

After Agent Porter befriends Maroney, he tells Pinkerton that Belle Maroney is a woman of such intelligence, strength, temperament, and will that she needs a shadow of her own. Pinkerton assigns one. Belle goes north to spend the summer in Jenkintown, PA, with her sister, and Pinkerton decides he should have an agent in the town to befriend her, gain her confidence, and pry from her whatever secrets she is holding.

This is where one of the story’s most interesting characters comes in. One day in Chicago, before the Maroney investigation started, a young widow, still in her twenties, walked into Pinkerton’s office and asked to be hired as a detective. Pinkerton told her there was no such thing as a woman detective, and she proceeded to tell him why there should be. This is Pinkerton’s description of the encounter:

I was seated one afternoon in my private office, pondering deeply over some matters, and arranging various plans, when a lady was shown in. She was above the medium height, slender, graceful in her movements, and perfectly self-possessed in her manner. I invited her to take a seat, and then observed that her features, although not what would be called handsome, were of a decidedly intellectual cast. Her eyes were very attractive, being dark blue, and filled with fire. She had a broad, honest face, which would cause one in distress instinctively to select her as a confidante, in whom to confide in time of sorrow, or from whom to seek consolation. She seemed possessed of the masculine attributes of firmness and decision, but to have brought all her faculties under complete control.

In a very pleasant tone she introduced herself as Mrs. Kate Warne, stating that she was a widow, and that she had come to inquire whether I would not employ her as a detective.

At this time female detectives were unheard of. I told her it was not the custom to employ women as detectives, but asked her what she thought she could do.

She replied that she could go and worm out secrets in many places to which it was impossible for male detectives to gain access. She had evidently given the matter much study, and gave many excellent reasons why she could be of service.

I finally became convinced that it would be a good idea to employ her. True, it was the first experiment of the sort that had ever been tried; but we live in a progressive age, and in a progressive country. I therefore determined at least to try it, feeling that Mrs. Warne was a splendid subject with whom to begin.

I told her to call the next day, and I would consider the matter, and inform her of my decision. The more I thought of it, the more convinced I became that the idea was a good one, and I determined to employ her. At the time appointed she called. I entered into an agreement with her, and soon after gave a case into her charge. She succeeded far beyond my utmost expectations, and I soon found her an invaluable acquisition to my force.

Warne, by the way, continued to work with Pinkerton through the Civil War, when he was Lincoln’s spy master. You don’t often see women on the battle field in the 19th century, but here she is in Union uniform, looking strong and self-assured. (* Update Sept. 10, 2019: This may not be Kate Warne. See the note at the bottom of the page.)

Pinkerton sends Warne to Jenkintown, where she takes a room for the summer in Stemple’s Tavern and Inn, just a short walk from where Belle Maroney is staying with her sister. Warne pretends to be a Madame Imbert, on vacation with her young companion, Miss Johnson. She strikes up a friendship with Mrs. Maroney. They walk and talk daily, and frequently go to Philadelphia together. Madame Imbert begins to sense the burden of Belle Maroney’s secret and her feelings of isolation, but she also knows Mrs. Maroney is guarded and mistrustful, and that direct questioning of any kind will only raise her suspicion.

One day, when she knows Belle Maroney is following her on her errands in Philiadelphia, Madame Imbert exchanges $500 in out-of-town bank notes for local notes. Mrs. Maroney begins to believe Madame Imbert is harboring dark secrets of her own, and eventually gets Imbert to confess she is the wife of a convicted forger who is serving a long prison sentence in another state. Relieved to find this unexpected companion in misery, Belle Maroney slowly begins to open up.

Pinkerton and the Adams Vice President had hedged their bets on Belle Maroney. Pinkerton knew his Agent Warne could get information out of her, but the Adams executive thought that, since she was “a loose woman,” it would be quicker to have one of his own men seduce her. He chose a young messenger from the company’s Philadelphia office, a handsome playboy who owned a buggy and a pair of horses, which would be useful for shuttling Mrs. Maroney between Jenkintown and the city, providing opportunities for the two to have long, private conversations.

The Vice President told De Forest to spend the summer in Jenkintown, to make friends with Belle Maroney, and to report back to him all he learned. He did not tell De Forest why he was to report on this woman, nor was the handsome ladies’ man prepared for a woman as strikingly beautiful, intelligent, and strong as the one he found.

Pinkerton describes Belle Maroney as a “medium sized, rather slender brunette, with black flashing eyes, black hair, thin lips, and a rather voluptuously formed bust.” In many of his reports back to the company, all De Forest can talk about is how he has fallen madly in love with her. De Forest has no idea what pressures she is under, and finds her occasional moody behavior incomprehensible. Pinkerton describes one brief falling out, when Mrs. Maroney goes several days without speaking to De Forest:

The poor fellow had missed her sadly. She had parted from him in anger, and he felt cut to the quick by her cold treatment. He had at first determined to blot her memory from his heart, and for this purpose turned his attention to Miss Johnson, and tried to get up the same tender feeling for her with which Mrs. Maroney had inspired him, but he found it impossible. He missed Mrs. Maroney’s black flashing eye, one moment filled with tenderness, the next sparkling with laughter.

Then Mrs. Maroney had a freedom of manners that placed him at once at his ease, while Miss Johnson was rather prudish, quite sarcastic, and somehow he felt that he always made a fool of himself in her presence. Besides, Miss Johnson was marriageable, and much as De Forest loved the sex, he loved his freedom more. His morals were on a par with those of Sheridan’s son, who wittily asked his father, just after he had been lecturing him, and advising him to take a wife, “But, father, whose wife shall I take?”

Day after day passed wearily to him; Jenkintown without Mrs. Maroney was a dreary waste. He felt that “Absence makes the heart grow fonder,” so when Mrs. Maroney greeted him so heartily he was overjoyed.

While the agents in Jenkintown report on Belle, Pinkerton continues to receive reports from his agents in the South on her husband, who spends the early part of the summer drinking and whoring in Tennessee and Mississippi, and then returns to Montgomery and falls in love with a local farm girl.

When Maroney travels North on business and stops in Philadelphia, Pinkerton is surprised to learn that he and Belle have visited a justice of the peace to get married. (Although they had posed as husband and wife for years, they had never been properly married.) Pinkerton knew from his agents in the South that Nathan Maroney intended to dump his wife and run off with the farm girl, with whom he was clearly in love. The marriage in Philadelphia made no sense at first.

Pinkerton eventually figured out that Belle had pushed the marriage on Nathan because she wanted to be sure she got her share of the money and was never abandoned again. She managed to sell Maroney on the idea by reminding him that an unmarried woman could be compelled to testify against him in court, while his wife could not.

Pinkerton decided to use the wedding to his advantage. Maroney was a popular man in Montgomery and throughout the cities of the South, where his frequent rail travels earned him a great number of acquaintances. When the express company first charged him with theft in Montgomery, public sentiment was almost universally against Adams Express and for Maroney, who easily made bail with the help of his friends.

After the wedding, Pinkerton posted a notice in a number of Southern newspapers announcing the marriage of Nathan Maroney and Belle Irvin in Philadelphia. This news came as a shock to Maroney’s friends and acquaintances, who all assumed the couple had been married for years. The notice turned public sentiment against the Maroneys, and caused a shock to Mrs. Maroney when she returned to Montgomery to retrieve the cash her husband had hidden. Friends who had once been warm to her were now either cold or hostile. Belle Maroney had no idea the marriage notice had been posted until she visited the home of the couple’s old friend, Charlie May.

Detective Porter, who was shadowing her on her visit to Montgomery, reported the following to Pinkerton:

[Mrs. Maroney] called at Charlie May’s. Something unusual must have happened, as she left there in bitter anguish… She wore no veil and the traces of her grief were plainly visible. She returned to the hotel and went to her room…

Charlie [May] said that Mrs. Maroney had called on his wife, but had been roughly handled—tongued would be the proper word. Mrs. May informed her of what she had read and otherwise heard about her getting married at this late date.

Mrs. Maroney denied the report and declared that they had been married in Savannah long before; that they had afterwards lived in New Orleans, Augusta, Ga., and finally had settled in Montgomery.

Mrs. May replied that it was useless for her to try and live the report down; that the ladies of Montgomery had determined not to recognize her, and that she had been tabooed from society. Mrs. May grew wrathful and warned Mrs. Maroney to beware how she conducted herself toward Mr. May.

This is a particularly insidious move by Pinkerton to isolate and vilify a woman who didn’t actually take part in her husband’s crime, though she did become an accomplice after the fact. And according to the morals of the day, it was her duty to stick by her man, no matter what he did. So she was damned if she left him, and damned if she didn’t.

The pain of the social rejection and isolation Pinkerton inflicts on Belle Maroney helps drive her into the arms of Madame Imbert, the confidant he has supplied to receive her confession.

Nathan Maroney doesn’t have it any easier. Pinkerton uses his connections to get him locked up in New York, pending extradition to Alabama. There’s still no evidence against him, and no one has seen the stolen money. Pinkerton plants an agent named John White in the jail to befriend Maroney and draw out his secrets. White and Kate Warne employ similar tactics to attract the suspects to them: they both appear preoccupied and somewhat aloof. They understand that their targets, criminals with guilty consciences, will be more likely to approach someone who also appears to be on the margins of society and who appears to have no interest in them (which, in the criminal world, translates to “no angle on them”). It also helps that both Warne and White appear to be criminals in trouble. They can naturally sympathize with other criminals in trouble.

Pinkerton tries to divide Maroney from his wife, writing an anonymous letter that says Mrs. Maroney is having an affair with De Forest back in Jenkintown. The helplessness and betrayal Maroney feels on reading this letter almost drive him mad, and White, his jail-house confidante, rubs it in by insisting Maroney should have expected as much, because no woman is ever trustworthy. As Maroney’s isolation and distress increase, he unburdens himself more and more to White.

Pinkerton’s tactics are similar to the ones we see today in detective movies, noirs, and police procedurals. The cops try to convince the suspects that their partners have turned against them, then they provide a sympathetic ear for the isolated and weakening suspect. Pinkerton used these tactics to great effect, and helped make them popular.

Both Mr. and Mrs. Maroney prove tough to crack, even under immense pressure. Kate Warne, posing as Madame Imbert, must use all her powers to seduce a confession from Belle Maroney. And seduce is the right word here. It’s not a sexual seduction, but a psychological one (which is always the necessary precursor to the sexual seduction). Rather than trying to pull information out of her target, Warne manipulates her into wanting to give it. In some ways, Warne is the archetype of the femme fatale in modern detective and noir novels. She can inspire feelings of ambivalence in readers, who will sympathize with her mission and admire her strength, while feeling uneasy about her duplicity and the way she manipulates, from her position of veiled power, a trapped woman who does not fully understand her current position of weakness.

Back in the Eldridge Street Jail in New York, as White is nearing release, Maroney begins to worry at the loss of his one and only confidante. He knows White is crafty, and believes him to be trustworthy. Maroney finally tells him he did steal the money, and he offers White a cut if White will help him frame another messenger for the crime. White agrees. They make a plan in which White will collect the cash from Mrs. Maroney in Jenkintown (the cash is buried in the cellar of her sister’s house), then plant some of the money and an Adams Express key on the other messenger back in Montgomery. (Remember that, in the 1850’s, most currency was in the form of notes issues by individual banks, so it was easier to tie specific notes to a specific theft.) White will have the crooked Montgomery detective arrest the messenger and discover they key and the cash.

When he gets out of jail, White never leaves New York, except to go to Jenkintown to pick up the cash from Mrs. Maroney, which he immediately hands over to Pinkerton and Adams Express. White then sends letters to Adams Express messengers in the South, who then deposit them in the local mail. Those letters, postmarked from towns along the way to Montgomery, go back to Maroney, still in jail in New York. Each letter says that another stage of the plan is complete, and Maroney can at last begin to taste his freedom.

It’s no spoiler to say that Pinkerton gets his man in the end. After all, in the procedural genre, we know who’s guilty from the start. The story is about how they were brought to justice. And poor Nathan Maroney believes he’s going to walk free all the way up until the last minute of his trial. Adams Express and the Montgomery detectives present their case over several days (although the book says it’s one day). A number of witnesses provide circumstantial evidence against Maroney, but it’s not strong enough to warrant a conviction.

Then, just before the defense rests, they call a surprise witness: a Mr. John R. White, detective. Maroney, knowing he’s done, breaks down and confesses in open court. The judge sentences him to 10 years hard labor. (With the harsh conditions and short life spans of the 19th century, that might have been a death sentence for a 30 year old man.)

Mrs. Maroney’s fate is left up in the air. Just before the trial, when Nathan Maroney still believes he’s going to get away with the money, John White, presumably on Pinkerton’s instructions, starts pushing Maroney to send his wife to Chicago. Jenkintown, he says, is too close to Adams Express headquarters in Philadelphia, and the company likely has its spies watching her. Maroney sends a letter to his wife repeating the argument, and this convinces her to move to Chicago.

Belle, nearing emotional collapse, will do anything anyone says at this point. She begs Madame Imbert to move to Chicago with her, and Madame Imbert agrees. Pinkerton notes that Kate Warne is also close to collapse, as her months in the role of confidante, and the exertion required of one very strong woman to break another very strong woman have taken everything out of her.

Before describing Nathan Maroney’s final fall, Pinkerton disposes of the women with this brief paragraph:

I had a house in Chicago, where I lodged my female detectives, and as I had only two in the city at the time, I easily found them a boarding-house, and turned the house over to Madam Imbert. The servants were well trained, and understood their business thoroughly. Everything being arranged, Madam Imbert wrote to Mrs. Maroney and Miss Johnson, telling them to come on. Two weeks after, Mrs. Maroney, Miss Johnson, and Flora arrived in Chicago, and took up their quarters with Madam Imbert.

I really wonder what happened in that house in Chicago. Did Kate Warne reveal her true identity to Belle Maroney? And what happened to Belle and her daughter in the years that followed?

Anoyone want to write that book?

In addition to being a fascinating period piece and a suspenseful crime drama, the story unintentionally highlights the razor-thin line between cop and criminal. Here are Times-Picayune reporter’s remarks on Pinkerton’s ability to out-deceive a master deceiver:

The Chicago policeman has so thoroughly mastered the theory and practice and practice of roguedom, that it must be a blessing to the community that he never turned rogue himself. He who knows so well all the weak points where the rascals open themselves to detection, would be the most dangerous of men, if nature had not made him honest.

Pinkerton himself doesn’t actually claim to be honest. He’s pretty open about how deceitful and conniving he is in this case.

At one point in the story, Pinkerton himself notes how fine he believes the line to be between the honest and the fallen. His agent, White, has just got the cash from Mrs. Maroney. He’s alone, carrying a leather satchel containing $40,000 in bank notes along a two-mile stretch of road between Belle’s sister’s house and an inn where he’s supposed to meet Pinkerton and the Adams Vice President. Pinkerton doesn’t wait for White at the inn. He stalks him the entire way because, he says, he fears the temptation of being alone with that much money might be too strong for any man.

In stating that he doesn’t quite trust his own otherwise trusted and proven agent, Pinkerton acknowledges that any person might have succumbed to the temptation that seduced Nathan Maroney. It’s hard not to have a little feeling for a pair done in by a moment of temptation, who has no idea what a vast conspiracy is afoot against them, who is so clearly trapped, deluded, and doomed. But Pinkerton intends to stir some discomfort in the reader. Near the end of the book, he writes:

The Divine administers consolation to the soul; the physician strives to relieve the pains of the body; while the detective cleanses society from its impurities, makes crime hideous by dragging it to light, when it would otherwise thrive in darkness, and generally improves mankind by proving that wrong acts, no matter how skillfully covered up, are sure to be found out, and their perpetrators punished. The great preventive of crime, is the fear of detection.

You can get The Expressman and the Detective free from Project Gutenberg in a number of formats.

A contemporary account of Maroney’s trial appears on page 11 of The New York Times of December 16, 1859, and provices more detail than the final pages of Pinkerton’s book. Sections of the more lengthy Picayune article are reprinted in New Hampshire Statesman of July 14, 1860 and a number of other papers.

A Note on the Photo of Kate Warne

From reader Corey Recko, Sept. 10, 2019

The photo isn’t actually of Kate Warne. The person in the original photo is unidentified, however, the photo was taken in early 1864, by which time Kate Warne was no longer involved with the military. Pinkerton left military service with McClellan’s dismissal in 1862. For the remainder of the war they worked for the US government investigating fraud and military claims.

The reason the photo is sometimes mistakenly identified as Warne is the presence of John C. Babcock (second from left). Around 2000, someone mistakenly identified another photo of Babcock as Kate Warne. As this was debated in online forms and other places, other images of Babcock were shared for comparison, and for some reason someone thought the unidentified person in the first photo looked female, and because of that it spread.