Ireland, June 2016

I arrived in Dublin on June 12 for the 2016 Open Repositories conference at Trinity College. By coincidence, my brother Paul arrived the same day from Seattle, on unrelated work, and had a room in the same hotel, two doors down the hall from mine. We met in the lobby around 5pm and were approached immediately by a drunk American woman in her 60s who asked Paul where his wife was. When he said she was at home, the woman said, “Well then, maybe you’d like to join me for a drink.” (She already had one in her hand.) Paul said no thanks, and the woman turned to me and asked where my wife was. Also at home. She invited me for drink, but I declined. Then she started cursing the “eighty year old losers” in her tour group and walked off, but not before reminding us both that we could find her at the pub next door at 8pm.

The pub next door was The Bleeding Horse, though the sign says something a little different.

The Bleeding Horse is a bustling place, and I had my first pint of Guinness there. It’s true what they say: it does taste better in Ireland. I’ve been a big fan of Guinness for years. I even named our first dog after the beer. In the US, Guinness has a faint hint of bitterness, which may come from being pasteurized. In Ireland, it’s smoother and sweeter. Not sweet like sugar, but sweet like cream or pure, cool water.

I was surprised at how close some Irish accents sound to American accents. Many people here sound like they grew up in Maryland or Pennsylvania. A local told me they call it “the mid-Atlantic accent,” and you only find it around Dublin. There are many other accents in Dublin as well, and once you leave the city, the accents change substantially from one town to the next.

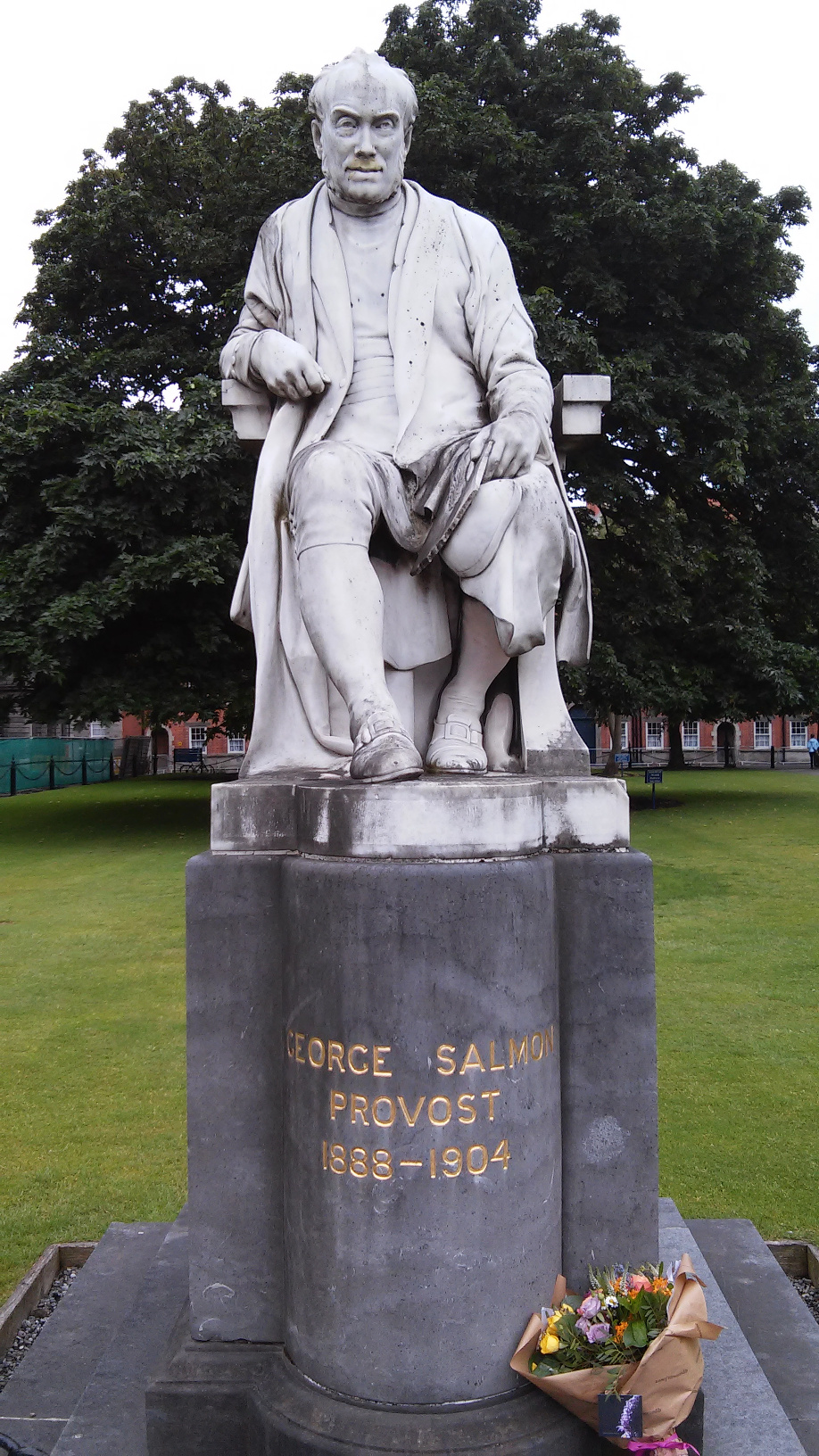

Another thing that struck me was this statue of George Salmon at Trinity College.

Salmon was the provost of Trinity College, and his statue occupies a place of honor, just inside the main gate. Statues of leaders in England, France, and the US generally try to portray a sense of energy, strength, nobility and grandeur, as if the subject were a visionary, larger than life and above the fray of common strife. This statue makes no such pretensions.

The man’s posture is slack, but his face is attentive and benevolent. You can see the accumulated weight of daily cares in his face and in his slightly disheveled dress. Maybe his appearance isn’t as important as his actions, his attitudes toward others, and his willingness to be a part of life’s struggles alongside everyone else. This man has been entrusted with power and influence, and he is clearly not “above it all.”

The entrance to the dining hall near the statue displays this quote from the Irish surgeon Denis Burkitt:

Attitudes are more important than abilities, motives are more important than methods, character is more important than cleverness, and the heart takes precedence over the head.

This isn’t a nation the celebrates power. Not in its public art, anyway. As Jonathan Swift wrote centuries ago:

Poor nations are hungry, and rich nations are proud, and pride and hunger will ever be at variance.

On a tour through Connemara yesterday, the guide described the great famine of 1845-1852. Irish peasants worked the land on the estates of British landowners, harvesting food they themselves couldn’t eat. The paid rent to the same landlords who employed them, the poorest of the poor survived mainly on the potatoes they grew themselves.

When the potato crop failed due to blight, the people had nothing to eat. When they were too weak to work, they lost their meager incomes, and then their homes. Ireland had 8 million people in 1845, and lost a million to starvation and another million to emigration over the next few years. The population never really recovered. Today it’s still around 6 million.

The tour guide noted that, while the potato crop was wiped out by blight several years in a row, other crops and agricultural products (beef, lamb, etc.) did not fail. But those were shipped to England, under armed guard, along the roads and through the ports where the people who harvested them were starving. That’s a pretty stark image of how capitalism and colonialism work.

If you want some more images, take a look at these. The first is of Kylemore Abbey, in Connemara.

This was a private home built by a wealthy British industrialist for his wife. Construction started in 1867, in a region of Connemara that was once home to about 500 people per square mile. After the famine, it was almost empty. Even now, there are more sheep in the region than people.

And here is a group of sculptures from central Dublin, showing what life was like for the masses in those years when Cannemara was emptying out. This is the most haunting and moving public art installation I have ever seen. I won’t comment, because the images speak for themselves. But it says a lot about a country and a people, when they are willing to acknowledge this right in the heart of their richest city, in an area surrounded by banks and upscale shopping.

These are stark images of a tragedy that cultures and institutions conspired to let happen not so long ago. It was the result of a system of laws and institutions designed specifically to ensure the flow of wealth in one direction, and a culture that reinforced the moral stigma of poverty to overcome natural human sympathy and decency.

I work in the tech industry, and I see all this happening again. Knowledge and information, which are the capital and currency of the 21st century, flow from all directions to a handful of powerful players who keep getting richer in the winner-take-all tech economy. Meanwhile, those who aren’t prepared for, or can’t conform to the world of thinking machines find themselves working harder and harder for less and less.

I look at those sculptures, and I hope it never comes to that again. But we certainly haven’t set things up to prevent it.